An Introduction to Systems Thinking in Road Safety

Authors

Paul M. Salmon, University of the Sunshine Coast

Gemma J. M. Read, University of the Sunshine Coast

Acknowledgements

Review names here

Abstract

Road crashes emerge from the complex interplay of factors across the road transport system, influenced by the social, political and economic context. While traditionally crashes have been attributed to proximal causes such as road user ‘errors’, recently it has been recognised that crashes emerge from the interactions between decisions and actions made by stakeholders across the whole road transport system (e.g., designers, managers, policy makers), including decisions made months and years prior to a crash occurring. Translation of this ‘systems thinking’ perspective in road safety practice is critical to ensure that current unacceptable rates of road trauma are reduced. The aim of this chapter is to present an overview of the systems thinking approach to road safety, including a discussion of key principles of systems thinking, how these apply in the road safety context, and how they can be used to drive systemic change. We present a series of case studies and discuss how systemic interventions, as opposed to more traditional road user-centric interventions (e.g., education, enforcement) can provide more wide-reaching and sustainable road safety outcomes.

1. Introduction

The past decade has seen a philosophical shift in road safety research and practice toward a ‘systems thinking’ approach. This shift was initiated based on the argument that traditional road safety approaches do not consider the inherent complexity of road transport systems and are overly reliant on road user-focused interventions such as engineering improvements, enforcement, and education (Larsson et al., 2010; Salmon et al., 2012; 2017). It followed a shift in the broader area of safety science from a focus on preventing human errors to a focus on managing risk from a systems thinking perspective (Read et al. 2021). Proponents of the systems thinking approach to road safety argued that, whilst significant progress had been made in reducing road crashes and road trauma, the traditional road user-focused interventions were unable to address the longstanding, complex issues that underlie many road safety challenges (Salmon et al., 2019). Given increasing adoption of advanced technologies, population growth, and an expanding set of societal issues, it was suggested that an increase in road crashes, injuries, and fatalities was likely if an alternative road safety approach was not adopted. Systems thinking was proposed as a suitable approach to manage road transport system risks and achieve sustainable reductions in road trauma (Salmon et al., 2012).

Systems thinking is a philosophy that is applied to understand and respond to complex problems in areas such as safety and public health (Salmon et al., 2023). It is based on the idea that adverse events (e.g., road crashes) are created by interactions between multiple system ‘components’, some of which are proximal to the event (e.g., road users, vehicles, road infrastructure), and some of which are distal (e.g., road rules and regulations, design standards, policies and procedures, and societal issues). System thinking proponents argue that it is not possible to fully understand and prevent road crashes without examining and understanding interactions across the entire road transport system. This involves looking beyond road users, their vehicles, and the road environment (the so-called ‘sharp-end’) to go ‘up and out’ (Dekker, 2011) and consider factors within the broader transport, social, and political system (Salmon et al., 2019).

Since initial calls to embed systems thinking in road safety research and practice (e.g., Larsson et al., 2010; Salmon et al., 2012), a growing body of research has applied the approach to understand and respond to recurring road safety issues (e.g. Hamim et al., 2021; Keller et al., 2025; McIlroy et al., 2019; Newnam et al., 2017; Salmon et al., 2013; 2019; 2020; Scott-Parker et al., 2015; Stanton et al., 2019; 2023; Young & Salmon, 2015). Though the approach is gaining traction in road safety with aspects beginning to appear in road safety strategies (e.g., Queensland Government, 2022) further work is required to embed the approach within road safety practice. In particular, there is a need support uptake of core principles and methods in road safety practice. The aim of this chapter is to present an overview of the systems thinking approach to road safety, including a discussion of key principles of systems thinking, how these apply in the road safety context, and how they can be used to drive systemic change. The intention is to support further adoption and translation of the systems thinking approach in road safety practice.

2. An introduction to systems thinking

- Systems and systems thinking

A system can be considered as “any group of interacting, interrelated, or interdependent parts that form a complex and unified whole that has a specific purpose” (Kim, 1999). According to Meadows (2008), systems comprise three core elements: components, interconnections, and a function or purpose. Road transport systems comprise components such as road users, vehicles, the road infrastructure, road rules and regulations, road user training and education materials, policies and procedures, budgets, strategy documents, and road safety stakeholders to name only a few. The purposes of road transport systems can be considered as being to provide access to work, recreational and social activities, and to support economic growth (Preston, 2001; Headicar, 2009; Salmon et al., 2019) and these purposes are achieved through continuous interactions between system components (Larsson et al., 2011; Salmon et al., 2012). These include interactions between road users and other road users, road users and vehicles, and between vehicles and the road infrastructure. They also include interactions between road designers and design standards, between trainers and educators and road users, between policy makers and researchers, and so on (Salmon & Read, 2026).

Systems thinking represents a “a way of seeing and talking about reality that helps us better understand and work with systems to influence the quality of our lives” (Kim, 1999). Specifically, systems thinking provides a way of thinking about road transport systems that can help us to (a) understand them and why they behave as they do, and (b) optimise their performance and the safety, health and wellbeing of those interacting within them (Salmon et al., 2023). Various systems thinking models, frameworks, and analysis methods are available to support this (see Salmon et al., 2022).

- A systems thinking model

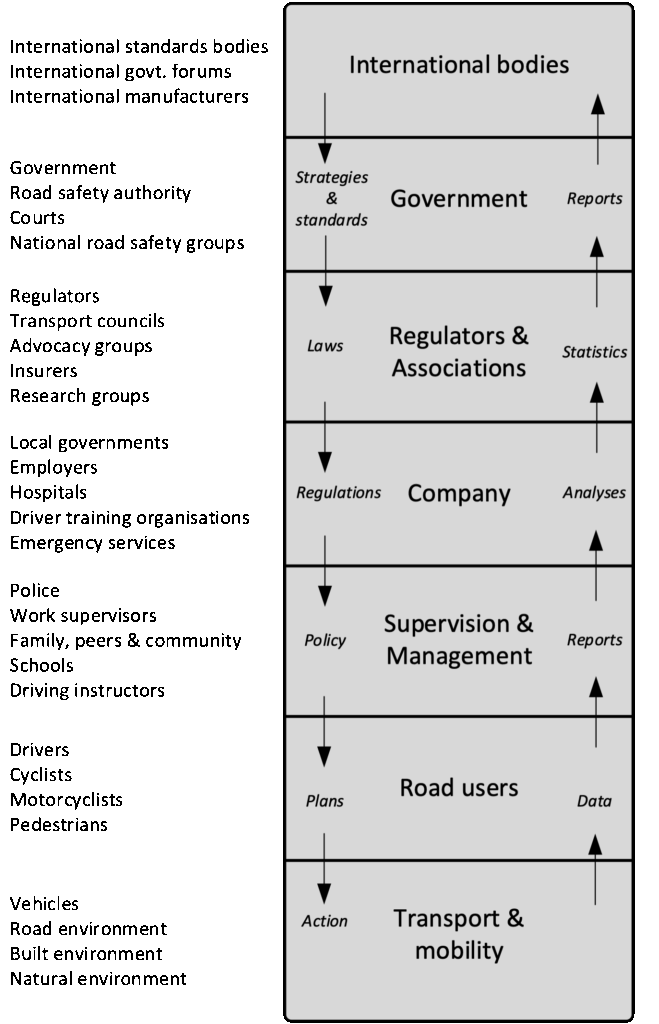

While there are various systems thinking models available, Rasmussen’s Risk Management Framework (RMF) (see Figure 1) has received the most use in road safety applications. As shown in Figure 1, the framework is based on the idea that complex systems comprise various hierarchical levels (e.g., governments, regulators, company, company management, staff, and work) and actors (e.g., individuals, organisations, or technologies as outlined on the left-hand side of Figure 1) who share the responsibility for performance and safety. The activities undertaken by these actors interact to influence system behaviour and outcomes, meaning that both safety and adverse events are created by all actors, not just those at the sharp-end (e.g., road users). The notion of a shared responsibility for safety is acknowledged within road safety and is a key principle of the current safe system approach (Hughes et al., 2015).

Figure 1. Rasmussen’s risk management framework modified for road transport (Salmon & Read, 2026).

A key principle of Rasmussen’s risk management framework is that adverse events are caused by multiple contributing factors, not just one bad decision or action. For road safety specifically, this suggests a need to look beyond road user behaviour and proximal events when attempting to understand the causes of road crashes. An implication is that it is not possible to fully understand road crashes by examining road users, their vehicles, or the road environment in isolation; rather, how interactions between all road transport system components create road crashes should be considered (Salmon & Read, 2026).

Rasmussen’s risk management framework is underpinned by a set of predictions regarding adverse event causation (Cassano-Piche et al., 2009). These have been modified as follows to fit the road safety context (Salmon & Lenne, 2015; Salmon & Read, 2026).

- Road safety and road crashes are emergent properties that are created by the decisions and actions of all road transport system stakeholders, not just road users alone;

- Road crashes are caused by multiple contributing factors from across the road transport system hierarchy, not just a single poor decision or action made by road users at the sharp-end;

- Road crashes can arise from a lack of communication and feedback across levels of the road transport system, not just from deficiencies at one level alone;

- Behaviours within road transport systems are not static, they migrate over time and under the influence of various pressures such as demand, financial constraints, psychological pressures, and societal issues (e.g., cost of living crises, alcohol addiction);

- Behavioural migration (i.e., changes in road transport stakeholder and road user behaviour caused by external pressures) occurs at multiple levels of road transport systems;

- Behavioural migration exposes weaknesses in road transport system defences, or cause defences to degrade and erode gradually over time. Road crashes are caused by a combination of this migration (e.g., a degradation in road maintenance practices) and a triggering event (e.g., a cyclist moving into the path of a vehicle when attempting to avoid a pothole).

Rasmussen also outlined the Accident Mapping (AcciMap) technique, which is an incident analysis method that is used to graphically represent incident contributory factors and the interactions between them. In line with Rasmussen’s RMF AcciMap is based on the idea that that behaviour, safety and accidents are emergent properties created by the decisions and actions of all stakeholders within a system, not just by front line workers alone (Cassano-Piche et al, 2009). Typically, six hierarchical levels are used: government policy and budgeting; regulatory bodies and associations; local area government planning & budgeting; technical and operational management; physical processes and actor activities; and equipment and surroundings. Contributory factors are identified, mapped to one of the six levels, and then linked between and across levels based on cause-effect relations (Salmon et al., 2023a).

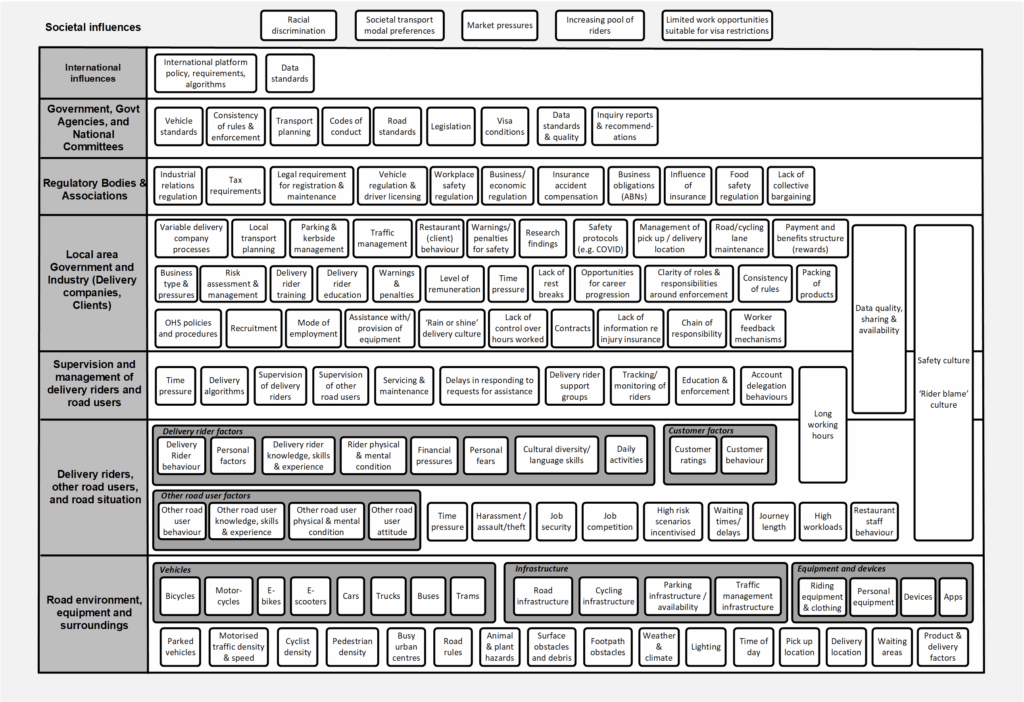

Various applications of Rasmussen’s RMF and AcciMap method have demonstrated the complex and systemic nature of road crash causation in different contexts (e.g., Newnam et al., 2017; Salmon et al., 2013; Stanton et al., 2019). For example, in Salmon et al. (2023b) we present an AcciMap analysis of stakeholder perceptions of the factors that influence ‘gig economy delivery rider behaviour and safety in Victoria, Australia (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. AcciMap showing stakeholder perceptions of the factors that influence gig economy delivery rider behaviour and safety (Source: Salmon et al., 2022).

As shown in Figure 2, stakeholders reported a diverse set of factors across all levels of the gig economy delivery rider system in Victoria, Australia. These factors can be grouped into the following areas (Salmon et al., 2023b):

- The delivery task. Includes factors relating to the delivery task itself, such as the product being delivered, high delivery rider workloads, delivery time pressure, the requirement to work in unfamiliar environments, and issues with vehicles and equipment (Salmon et al., 2023b).

- The workforce. Includes factors relating to the delivery rider workforce, such as personal factors, knowledge skills and experience, risk taking behaviours, rider physical and mental condition (e.g., fatigue), cultural factors, and financial pressures (Salmon et al., 2023b).

- Apps, algorithms, and data. Includes factors relating to delivery apps and their algorithms as well as other apps used by delivery riders use such as navigation apps (Salmon et al., 2023b).

- Infrastructure. Includes factors associated with the infrastructure used by delivery riders, including limited cycling infrastructure (e.g., bicycle lanes), poorly designed road infrastructure (e.g., intersections), a lack of parking, and issues in the built environment, pick-up, and delivery locations (e.g., Salmon et al., 2023b).

- Cultural and social influences. Includes cultural and social influences on delivery rider behaviour and safety, safety culture in delivery companies and client organisations (e.g., restaurants), and a general societal culture of racial discrimination (Salmon et al., 2023b).

- Clients, customers, and other road users. Includes factors relating to customers (e.g., customer ratings, customer behaviour), delivery clients (e.g., restaurant staff), and other road users (e.g., attitudes towards delivery riders, interactions with delivery riders) (Salmon et al., 2023b)

- Delivery platform processes. Includes factors relating to the processes employed by delivery companies (e.g., policies and procedures, recruitment and onboarding processes, rider training and education, risk management) (Salmon et al., 2023b).

- Laws and regulations. A number of the factors placed at the higher levels of the AcciMap relate to the laws and regulations either currently in place or where gaps exist in laws and regulation such as industrial relations regulation, vehicle regulation and licensing, workplace safety regulation, business and economic regulation and food safety regulation (Salmon et al., 2023b).

3. What is causing road trauma?

The systems thinking approach has two key implications when attempting to understand crash causation. The first is that crash contributory factors will span multiple actors and levels of the road transport system, and the second is that crash contributory factors will interact with and influence one another.

3.1 Road crash contributory factors

There is a strong body of evidence describing road crash contributory factors relating to individual road users, vehicles, and the road environment (e.g., Parker et al., 1995; Reason et al., 1990; Sabey & Taylor, 1980; Treat et al., 1979; Wagenaar & Reason, 1990). The application of systems thinking in road safety has expanded knowledge on the causes of road trauma to include insight into the role of contributory factors beyond road users, their vehicle, and the road environment. These include contributory factors relating to societal norms, government, vehicle and road designers, road rules and regulations, design standards and processes, road authorities, land use design and urban planning, technology designers, the media, and employers (Newnam et al., 2017; Salmon et al., 2019). This body of work suggests that, although road users engage in behaviours that play a direct causal role in road crashes and trauma, a range of factors across road transport and society interact to create these behaviours (Salmon et al., 2020). Rather than be considered the primary cause of road crashes, road user ‘errors’ should instead be considered a consequence of interactions occurring in the broader road transport system and across society. This points to the need to reform road safety strategies (Hughes et al., 2016) and develop new forms of intervention beyond engineering, education, and enforcement (McIlroy et al., 2019; Salmon et al., 2019).

3.1.1 Interactions between road crash contributory factors

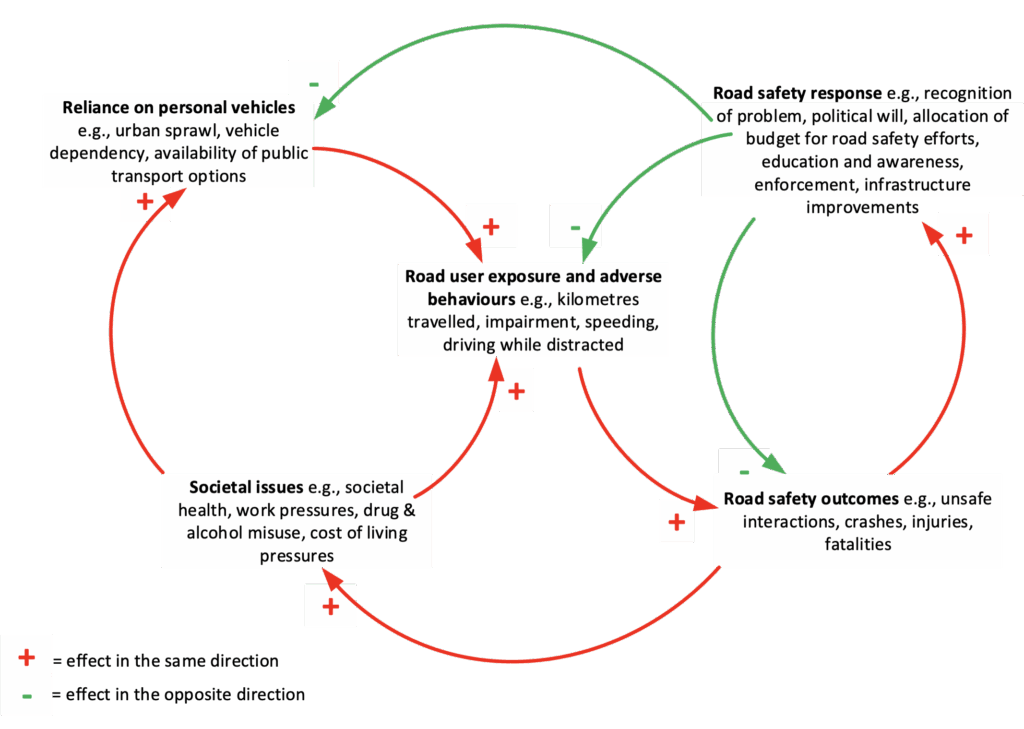

A simple Causal Loop Diagram (CLD) can be used to demonstrate how contributory factors interact to create road trauma. CLDs are a systems thinking method that can be used to describe the positive and negative feedback loops that interact to influence system behaviour. CLD models comprise variables connected by arrows which depict the causal influences between the variables (Sterman, 2000). Two kinds of loop are considered: positive, or reinforcing loops, and negative, or balancing loops. Positive feedback loops are self-reinforcing; for example, if you consider feedback loops relating to population growth as births increase, the population increases, which in turn leads to an increase in the birth rate, which in turn increases the population, and would further increase the birth rate and so on. Negative loops are self-correcting; for example, as the population increases, the death rate increases and acts as a balance on population growth. These simple positive and negative feedback loops are presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Positive and negative feedback loops influencing population growth. R = Reinforcing loop, B = Balancing loop.

Understanding the interactions between positive and negative feedback loops is critical for understanding complex issues such as road trauma. A simplified CLD for road trauma is presented in Figure 4. The simplified CLD shows how five categories of factors interact to create road trauma: societal issues (e.g., societal health, drug and alcohol misuse, work pressures), reliance on personal vehicles (e.g., dependency on personal vehicles, availability of public transport services), road user exposure and behaviour (e.g., exposure for different road users, speeding, distraction, impairment), road safety outcomes (e.g., unsafe interactions, crashes, injuries and fatalities), and the road safety response (e.g., recognition of problem, political will, road safety education and awareness, enforcement).

As shown in Figure 4, a reliance on personal vehicles based on urban sprawl and a lack of alternative transport options has the effect of increasing levels of road user exposure (e.g., number of road users and the kilometres travelled), whilst societal issues such as drug and alcohol misuse, work and societal pressures, and poor health influence road users’ engagement in unsafe behaviours such as drink driving, driving under the influence of drugs, speeding, and driving whilst fatigued. Increases in road user exposure and adverse road user behaviours create unsafe interactions on the road, some of which result in crashes, injuries and fatalities. As crashes, injuries, and fatalities rise, the gap between the goal state (i.e., road safety targets relating to crashes, injuries, and fatalities) and actual state increases, which in-turn heightens recognition of the problem and acts to increase the political will to intervene. As political will strengthens, more finances are allocated to road safety initiatives, which in turn act to reduce exposure, adverse road user behaviours, and negative road safety outcomes through initiatives such as education programs, increased enforcement, and improved road infrastructure.

An important feature of the CLD in Figure 4 is that factors are dynamic and are increasing or decreasing depending on the influence of other factors. For example, road safety response factors will increase following poor road safety outcomes but decrease once road safety outcomes start to improve. Similarly, worsening societal issues will create an increase in unsafe road user behaviours, whilst improvements will act to reduce the number of road users engaging unsafe behaviours. These dynamics are a critical consideration for road safety efforts and provide an explanation for fluctuating levels of road trauma in recent years (Salmon et al., 2020).

Figure 4. Simplified causal loop diagram showing the factors that interact to create road trauma

The CLD demonstrates that many influences on road user behaviour sit outside of the road transport system, including factors relating to societal health, drug and alcohol use, and work and societal pressures. However, as shown in the CLD, road safety response factors primarily act on road user behaviour and levels of road user exposure. Whilst interventions such as education and enforcement do have an effect, they cannot fully prevent crashes, injuries and fatalities as societal issues and a heavy reliance on personal vehicles will continue to create high levels of exposure and adverse road user behaviours.

4. Translating systems thinking in road safety practice

The systems thinking philosophy and its methods have a number of implications for road safety practice. In Salmon & Read (2026) we present recommendations designed to support the translation of systems thinking in road safety practice based on Read et al.’s (2021) recommendations for initiating a shift from human error-focused practice toward systems thinking in safety science generally. A summary of these recommendations is presented in Table 1. It is our view that the activities included in Table 1 form critical steps in supporting the translation of systems thinking in road safety practice.

Table 1. Recommended actions for road safety stakeholders (adapted from Salmon & Read, 2026).

5. Summary

The application of systems thinking in road safety has expanded knowledge on the causes of road trauma to include insight into the role of factors beyond road users, their vehicle, and the road environment (Salmon & Read, 2026). It is our view that the translation of key systems thinking principles in road safety practice will support the design and operation of safer and more efficient road transport systems. Whilst a significant body of work is required to effectively embed systems thinking within road safety practice, a key first step involves communicating core systems thinking principles to road safety practitioners. In this chapter we have outlined key systems thinking principles along with a set of recommended actions for road safety stakeholders. Though we acknowledge there is some way to go before systems thinking becomes embedded in road safety practice, we hope that the reader finds this chapter useful and that it helps to facilitate the translation systems thinking in road safety practice.

6. References

Australasian College of Road Safety. (2023). Policy position statement: a new systems thinking approach to road safety. https://acrs.org.au/wp-content/uploads/A-new-systems-thinking-approach-to-road-safety-FINAL.pdf, accessed 24th May 2024.

Cassano-Piche, A. L., Vicente, K. J., & Jamieson, G. A. (2009). A test of Rasmussen’s risk management framework in the food safety domain: BSE in the UK. Theoretical Issues in Ergonomics Science, 10(4), 283–304.

Dekker, S. (2011). Drift into failure: From hunting broken components to understanding complex systems. CRC press.

Hamim, O. F., Hoque, M. S., McIlroy, R. C., Plant, K. L., & Stanton, N. A. (2020). A sociotechnical approach to accident analysis in a low-income setting: using Accimaps to guide road safety recommendations in Bangladesh. Safety Science, 124, 104589.

Headicar, P. (2009). Transport policy and planning in Great Britain. Routledge.

Hughes, B. P., Anund, A., & Falkmer, T. (2015). System theory and safety models in Swedish, UK, Dutch and Australian road safety strategies. Accident Analysis & Prevention, 74, 271-278.

Hughes, B. P., Anund, A., Falkmer, T. (2016). A comprehensive conceptual framework for road safety strategies. Accident Analysis and Prevention, 90, 13-28

Keller, M. E., Watson, B., Kaye, S. A., King, M., & Lewis, I. (2025). Experts’ perspectives on shared responsibility for speed management: A thematic analysis informed by systems thinking. Accident Analysis & Prevention, 221, 108185.

Kim, D. H. (1999). Introduction to systems thinking. Pegasus Communications. Retrieved from https://thesystemsthinker.com/introduction-to-systems-thinking/

Larsson, P., Dekker, S.W.A., Tingvall, C. (2010). The need for a systems theory approach to road safety. Safety Science 48 (9), 1167–1174.

McClure, R.J., Adriazola-Steil, C., Mulvihill, C., Fitzharris, M., Bonnington, P., Salmon, P.M., Stevenson, M., 2015. Simulating the dynamic effect of land use and transport policies on the development and health of populations. American Journal of Public Health 105 (S2), 223–229.

McIlroy, R. C., Plant, K., Hoque, M.S., Wu, J., Kokwaro, G.O., Vu, N.H. and Stanton, N. A. (2019). Who is responsible for global road safety? A cross-cultural comparison of Actor Maps. Accident Analysis and Prevention, 122, 8-18.

Meadows, D. H. (2008). Thinking in systems: A primer. Chelsea Green Publishing.

Newnam, S., & Goode, N. (2015). Do not blame the driver: A systems analysis of the causes of road freight crashes. Accident Analysis & Prevention, 76, 141-151.

Newnam, S., Goode, N., Salmon, P., & Stevenson, M. (2017). Reforming the road freight transportation system using systems thinking: An investigation of Coronial inquests in Australia. Accident Analysis & Prevention, 101, 28-36.

Parker, D., Reason, J. T., Manstead, A. S., & Stradling, S. G. (1995). Driving errors, driving violations and accident involvement. Ergonomics, 38(5), 1036-1048.

Preston, J. (2001). Integrating transport with socio-economic activity–a research agenda for the new millennium. Journal of Transport Geography, 9(1), 13-24.

Queensland Government. (2022). Queensland Road Safety Strategy 2022 – 2031. https://www.publications.qld.gov.au/ckan-publications-attachments-prod/resources/d28d7b57-2e59-456c-810d-5a4cf9654ddb/queensland-road-safety-strategy-2022-31.pdf?ETag=86607f1e7ec3d5de14e64614325f9a19

Rasmussen, J. (1997). Risk management in a dynamic society: A modelling problem. Safety Science, 27:2/3, pp. 183-213.

Reason, J., 1997. Managing the risks of organisational accidents. Ashgate, Surrey, United Kingdom.

Read, G. J., Shorrock, S., Walker, G. H., & Salmon, P. M. (2021). State of science: evolving perspectives on ‘human error’. Ergonomics, 64(9), 1091-1114.

Reason, J., Manstead, A., Stradling, S., Baxter, J., & Campbell, K. (1990). Errors and violations on the roads: a real distinction?. Ergonomics, 33(10-11), 1315-1332.

Sabey, B. E., & Taylor, H. (1980). The known risks we run: the highway. In Societal risk assessment: How safe is safe enough? (pp. 43-70). Boston, MA: Springer US.

Salmon, P.M., Lenné, M.G., (2015). Miles away or just around the corner: systems thinking in road safety research and practice. Accident Analysis and Prevention 74, 243–249.

Salmon, P. M., Read, G. J. M. (2026). Systems Thinking in Road Safety Practice: An introduction. In M. Regan, R. Morgan, J. Campbell (Eds.). Human Factors Handbook for Road Designers and Traffic Engineers. CRC Press, Boca Raton.

Salmon, P.M., McClure, R., Stanton, N.A., (2012). Road transport in drift? Applying contemporary systems thinking to road safety. Safety Science 50 (9), 1829–1838.

Salmon, P. M., Read, G. J., Stanton, N. A., & Lenné, M. G. (2013). The crash at Kerang: Investigating systemic and psychological factors leading to unintentional non-compliance at rail level crossings. Accident Analysis & Prevention, 50, 1278-1288.

Salmon, P.M., Hulme, A., Read, G. J. M. (2023a). Systems and systems thinking. OHS Body of Knowledge, https://www.ohsbok.org.au/chapter-12-1-systems/#1548328004983-899b528e-01e4, accessed 24th May 2024.

Salmon, P. M., Bhawana, K. C., Irwin, B. G., Brennan, C. J., & Read, G. J. (2023b). What influences gig economy delivery rider behaviour and safety? A systems analysis. Safety Science, 166, 106263.

Salmon, P. M., Hulme, A., Read, G. J., Thompson, J., & McClure, R. (2017). Rethinking the causes of road trauma: society’s problems must share the blame. The Conversation, 29, https://theconversation.com/rethinking-the-causes-of-road-trauma-societys-problems-must-share-the-blame-82383

Salmon, P. M., Read, G. J., Thompson, J., McLean, S., & McClure, R. (2020). Computational modelling and systems ergonomics: a system dynamics model of drink driving-related trauma prevention. Ergonomics, 63(8), 965-980.

Salmon, P. M., Read, G. J., Beanland, V., Thompson, J., Filtness, A. J., Hulme, A., … & Johnston, I. (2019). Bad behaviour or societal failure? Perceptions of the factors contributing to drivers’ engagement in the fatal five driving behaviours. Applied ergonomics, 74, 162-171.

Salmon, P. M., Stanton, N. A., Walker, G. H., Hulme, A., Goode, N., Thompson, J., & Read, G. J. (2022). Handbook of systems thinking methods. CRC Press.

Scott-Parker, B., Goode, N., & Salmon, P. (2015). The driver, the road, the rules… and the rest? A systems-based approach to young driver road safety. Accident Analysis & Prevention, 74, 297-305.

Stanton, N. A., Salmon, P. M., Walker, G. H., & Stanton, M. (2019). Models and methods for collision analysis: A comparison study based on the Uber collision with a pedestrian. Safety Science, 120, 117-128.

Stanton, N. A., Box, E., Butler, M., Dale, M., Tomlinson, E. M., & Stanton, M. (2023). Using actor maps and AcciMaps for road safety investigations: development of taxonomies and meta-analyses. Safety Science, 158, 105975.