The History of Road Safety

Authors

Barry Watson, Queensland University of Technology

Judy Fleiter, The George Institute for Global Health

Acknowledgements

Margie Peden, The George Institute for Global Health

Reviewer names here

Abstract

This chapter overviews the history of road safety from the advent of the motor vehicle through to recent global developments. It explains how countries responded to the rise in road deaths and injuries, both in terms of the countermeasures introduced and the institutional arrangements put in place to deal with the problem. The initial focus is on countries that were early adopters of the motor vehicle and the first to experience the negative impacts of road crashes. These were typically high-income countries (HICs) that experienced rapid motorisation during the 1950s and 1960s, which further exacerbated the problem. Up until this time, government responses had primarily involved education and enforcement efforts targeting ‘irresponsible’ drivers, which were based on opinion and guesswork. Fortunately, during the 1970s and 1980s a more scientific approach emerged that was informed by public health principles. It led to a stronger focus on understanding the complexity of the factors contributing to road crashes and to the implementation of countermeasures designed to not only prevent crashes but also to reduce their severity. From this time, many HICs experienced dramatic reductions in road fatalities that were reinforced in the 1990s and 2000s through the adoption of strategic frameworks designed to better direct and coordinate road safety efforts. To illustrate the way that HICs responded to the road safety problem, an in-depth case study is provided of the Australian situation. The final part of the chapter deals with the escalation in road deaths and injuries that occurred in low- and middle-income countries towards the end of the 20th century. This led to road crashes being recognised as a global crisis requiring a coordinated response at the international level. The chapter closes with an overview of the lessons to be learnt from the history of road safety.

Key words

History of road safety

Road trauma

Traffic safety

Road crashes

Decade of Action for Road Safety

Sustainable Development Goals

Glossary terms

Countermeasure/intervention

GRSP – Global Road Safety Partnership

HIC – High-income country

LMIC – Low- and middle-income countries

UNRSC – United Nations Road Safety Collaboration

WHO – World Health Organization

Online Course Outline

This section of the course provides a foundation for the Body of Knowledge (BoK) by outlining the history of road safety, from the advent of the motor vehicle through to recent developments. It explains how countries responded to the growing problem of road deaths and injuries, both in terms of the countermeasures introduced and the institutional changes put in place to deal with the problem. The initial focus is on those countries that were early adopters of the motor vehicle and first experienced the negative impacts of road crashes. These were typically high-income countries (HICs) that experienced rapid motorisation during the 1950s and 1960s, which further exacerbated the problem. In response, during the 1970s and 1980s, a more scientific approach emerged that was informed by public health and epidemiological principles. As a result, many HICs experienced dramatic reductions in road fatalities that were reinforced in the 1990s and 2000s through the adoption of strategic frameworks designed to better direct and coordinate road safety efforts. To illustrate the way that HICs responded to the road safety problem, an in-depth case study is provided of the Australian situation. This is followed by an overview of the global road safety crisis that emerged at the end of the 20th century, when an escalation in road deaths and injuries occurred in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) due to rapid motorisation. An interactive timeline is provided that identifies the key developments in global road safety from this time. The key lessons to be learnt from the history of road safety are also identified.

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter / completing this section of the course, road safety professionals will be able to:

- understand the historical factors that have shaped responses to the global road safety problem, with particular emphasis on developments since the 1960s;

- identify the hallmarks of the scientific approach to road safety, which emerged in the 1970s;

- describe how road safety is currently addressed at the global level, including the role of the key international bodies, organisations and coalitions; and

- describe some of the key lessons learnt from the history of road safety.

1. Introduction

This chapter is designed to provide a foundation for the Body of Knowledge (BOK) by outlining the history of road safety, from the advent of the motor vehicle through to recent developments. It overviews the way that countries responded to the growing problem of road crashes and related deaths and injuries, both in terms of the countermeasures introduced and the institutional changes put in place to deal with the problem. A key objective of the chapter is to identify those approaches that have proven most effective in reducing road crashes and related trauma, both in terms of individual countermeasures and strategic programs of activity.

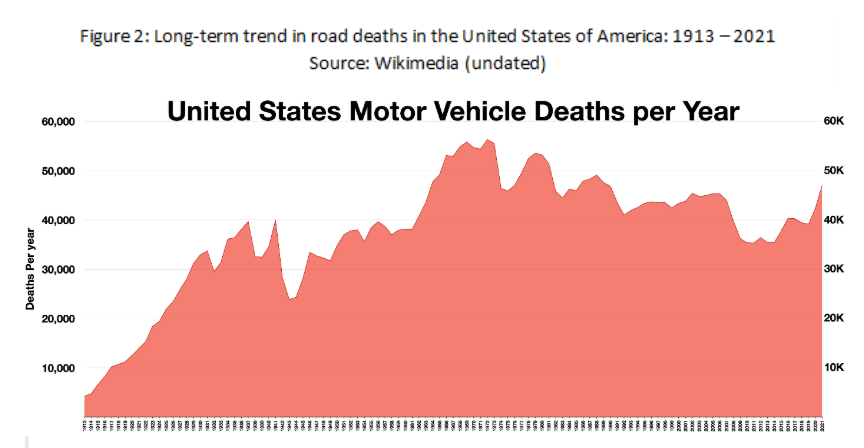

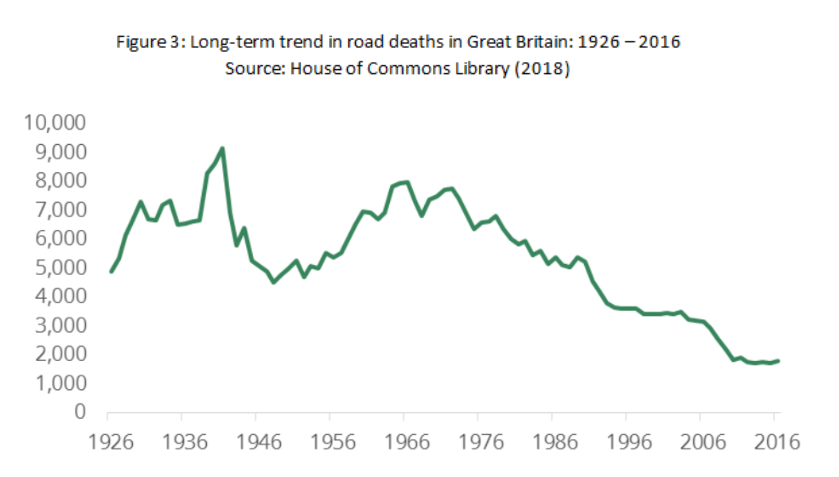

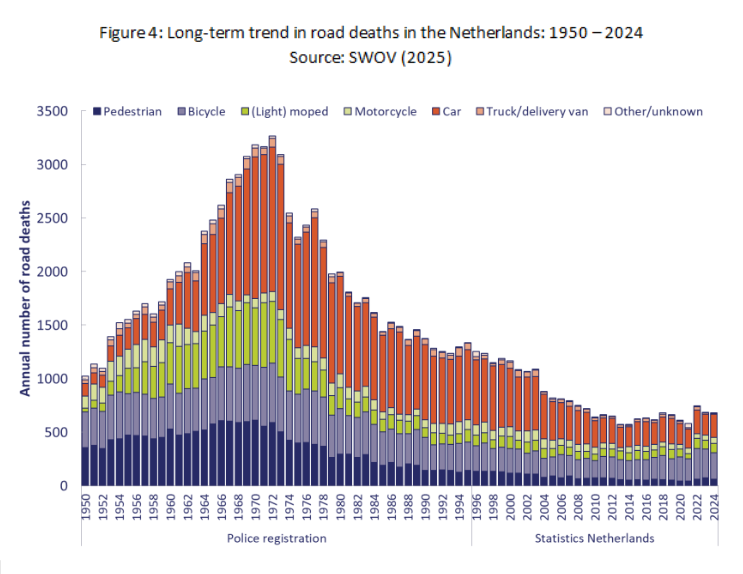

The first part of the chapter focuses on those countries that were early adopters of the motor vehicle, since they were the first to experience the negative impacts of road crashes. These were typically high-income countries (HICs) in North America, Europe and Australasia where deaths and injuries grew steadily in the first half of the 20th century, except for brief periods corresponding to the Great Depression and World War II (WWII). A general overview is then provided as to how these countries responded to growing community concerns about road safety, particularly from the 1950s and 1960s onwards when rapid motorisation led to an escalation in road deaths and injuries.

The second part of the chapter is an in-depth case study based on the Australian situation, designed to more closely examine the evolution of road safety policies and practices, as well as the philosophical and strategic frameworks underpinning road safety thinking and related actions. While this case study is specific to Australia, attention is given to the key international developments that influenced road safety in that country. The case study also identifies contemporary and emerging road safety challenges in Australia, which will be highly relevant to many countries.

The third part of the chapter focuses on the escalation of road deaths and injuries in low- and middle-income countries towards the end of the 20th century. This escalation led to road crashes being recognised as a global crisis requiring a coordinated response at the international level. An interactive timeline highlights the key institutional and strategic responses to this crisis, along with the stakeholders involved.

The chapter closes with an overview of the lessons to be learnt from the history of road safety and some reflections on the ongoing challenges in the field. While this chapter has been written to provide a standalone account of the history of road safety, it should ideally be read in conjunction with the next chapter that outlines the scale and nature of the global road safety crisis.

2. The impact of the motor vehicle in early adopter countries

“At the turn of the century, when the passenger car emerged upon the scene, Carl Benz is supposed to have considered that the market for his automobile was limited because ‘there were going to be no more than one million people capable of being trained as chauffeurs’” (Henderson, 1991, p. 7)

In many respects, the impact of motor vehicles on society was both unanticipated and pernicious. While various forms of steam- and electric-powered vehicles had been developed in the 18th and 19th centuries, the first practical car for everyday use was patented by Carl Benz in 1886 using a gasoline-powered combustion engine (Encyclopedia Britannica, undated). Shortly after this, inventors and entrepreneurs in Europe and America continued refining the design and production of gasoline-powered motor vehicles. In 1897, Ransom E. Olds founded the Oldsmobile company in Detroit and pioneered the use of the assembly line to produce motor vehicles on a larger scale. The Curved-Dash Oldsmobile was a light, reliable and relatively powerful vehicle that caused a sensation at the New York Auto Show in 1901 and went on to become the top-selling car in the USA between 1903–1904 (Historic Vehicles, undated). In 1908, the Ford Motor Company further refined the assembly line production of motor vehicles. Whereas the production of the Oldsmobile’s involved a static line around which workers moved, the Ford assembly line moved past static worker stations. This enabled Ford to sell the Model T car at the relatively modest price of US $850. Although this cost was still higher than an average American worker’s annual wage, it made ownership of a motor vehicle much more affordable for many. Indeed, between 1913 and 1927, Ford factories produced more than 15 million Model T cars (History.com, undated).

Initial concerns about motor vehicles centred around them scaring horses and pedestrians. However, the potential for them to lead to death and injuries quickly emerged. Although there had been instances of people being injured or killed by steam-powered automobiles, the first person killed by a gasoline-powered motor vehicle is generally recognised as being Bridget Driscoll (Bourne, 2025). She was a pedestrian who was struck and killed in 1896 by an Anglo-French car at Crystal Palace, London. The driver was arrested, although the death was ruled an ‘accident’ and he was not prosecuted. The presiding coroner was quoted as saying that he hoped “such a thing would never happen again” (Soniak, 2012, p.1). Unfortunately, this was not the case and fatalities and injuries continued to rise as motor vehicle sales and use increased.

Growing public concerns about road crashes prompted governments to commence introducing controls on motor vehicles from the early 20th century. In the USA, Connecticut became the first state to introduce a speed limit law for motor vehicles in 1901, while New York City adopted the world’s first comprehensive traffic code in 1903 (Bourne, 2025). However, the response to this growing public health problem was uneven across countries. Driver licences were first introduced in Britain in 1903, although they were primarily for the purposes of identifying drivers. Indeed, The Highway Code was not launched in Great Britain until 1931, by which time there were over 7,000 people being killed in road crashes each year (UK Driver & Vehicle Standards Agency, 2019).

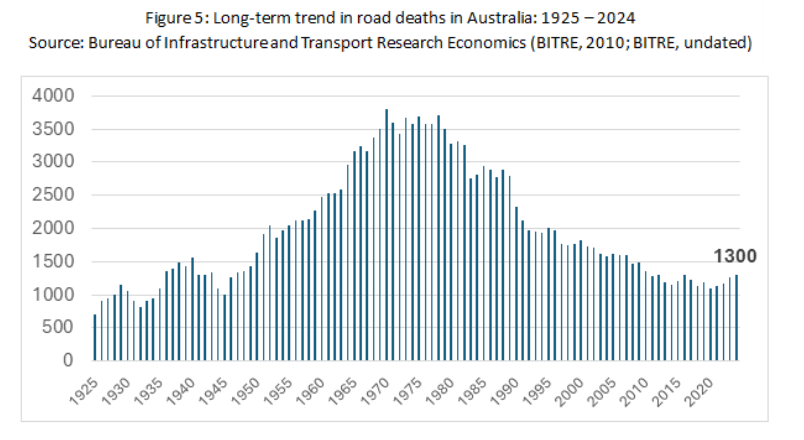

As the 20th century progressed, the way that jurisdictions responded to road crashes was influenced by many factors including: the pace of motorisation; historical developments impacting on road use; and the prevailing political and sociocultural circumstances. Nonetheless, commonalities can be seen among countries that were early adopters of the motor vehicle (which were typically high-income countries). To illustrate this, Figures 2 – 5 show the long-term trend in road deaths for the USA, Great Britain, the Netherlands and Australia. To aid in interpretation, the major developments discussed below are shown on the Australian graph.

In all four countries, there was a general increase in road deaths during the first half of the 20th century which only abated during the Great Depression and the WWII, when road transport was temporarily constrained. Interestingly, the reduction in deaths in Great Britain didn’t commence until 1941 since the wartime blackout contributed to a peak of over 9,000 fatalities in 1940 (House of Commons Library, 2018). During the 1950s and 1960s, all four countries experienced rapid motorisation accompanied by a major increase in road deaths, prompting growing concern among health professionals and the general community. Fortunately, this led to the adoption of a more scientific approach to road safety in the late 1960s and early 1970s, resulting in a dramatic decline in road deaths. During the 1990s and 2000s, the rate of decline in road deaths began to slow in all four countries, which prompted the adoption of a more strategic approach to road safety, guided by frameworks such as Vision Zero (in Sweden), Sustainable Safety (in the Netherlands) and the Safe System Approach (in Australia). In more recent years, road deaths have either plateaued or started to rise again in all four countries, particularly since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic.

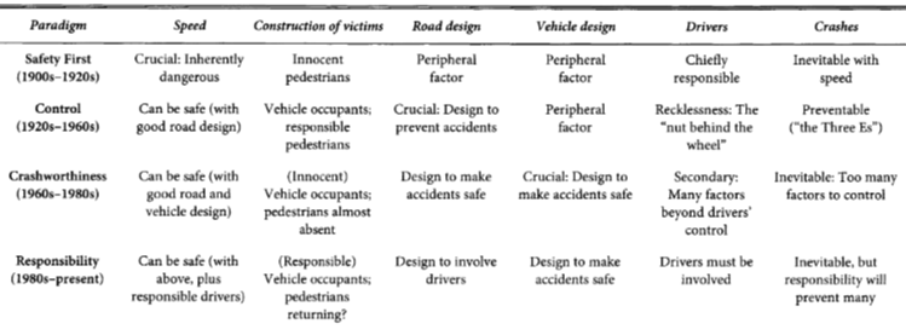

Based on developments in the USA, Norton (2015) argued that the history of road safety could be divided into four distinct time-based paradigms, distinguishable by how the problem was conceptualised and the responses that were adopted (see Table 1). In the first ‘Safety First’ paradigm (1900s – 1920s), crashes were typically viewed as being inevitable due to prevailing vehicle speeds, with drivers bearing primary responsibility. In the second ‘Control’ paradigm (1920s -1960s) there was growing recognition that crashes were preventable, particularly through efforts to discourage reckless driving behaviour. By the time of the third ‘Crashworthiness’ paradigm (1960s – 1980s), there was a growing belief that there were too many contributing factors to crashes that were beyond the control of the driver. As such, there was a need to make roads and vehicles more ‘crashworthy’ to mitigate crash severity. Finally, in the fourth paradigm, ‘Responsibility’ (1980s – present), there was greater emphasis on the need to involve drivers and other road users in efforts to prevent road crashes. Although the USA had yet to fully embrace the Safe System Approach (see section 3.5) at the time Norton (2015) was writing, this fourth paradigm appears to foreshadow the principle of shared responsibility which emphasises the need for all stakeholders involved in the operation of the road transport system to take responsibility for safety, not just road users.

Table 1: Four paradigms of traffic safety in the 20th century United States (Norton, 2015)

Although Norton’s (2015) proposed road safety paradigms were based on the US situation, they arguably hold for many other high-income countries that followed a similar trajectory. To explore this in greater detail, the next section provides an in-depth case study focusing on the history of road safety in Australia. The focus then turns to the global road safety crisis that emerged in the latter part of the 20th century when levels of motorisation began to rapidly climb in LMICs.

3. Case study: Road safety in Australia

3.1 Early responses to the rise in motor vehicles and related crashes

Similar to other countries, early concerns about motor vehicles in Australia were closely related to their speed and impact on other road users. As noted by Clark (1999, p.2), “. . . the new motor cars were travelling on roads still dominated by, and far better suited to, horsedrawn and pedestrian traffic. The first motor cars were exciting in their novelty but also noisy, unpredictable and much faster than horse traffic”. In response to these concerns, the Australian state governments began introducing traffic laws to regulate motor vehicles in the first decade of the 20th century. Clark (1999) argues that a key feature underpinning this legislation was the concept of ‘reckless’ or ‘negligent’ driving and that this focus on self-regulation reflected a desire to not impede the growth of the automobile manufacturing sector or limit the more efficient movement of people and goods. While the states introduced vehicle registration and driver licence requirements, these were primarily for administrative purposes such as road funding and driver identification (Watson, 2024). As noted by Clark (1999, p.3), “in the early years of the twentieth century restrictions on motoring were few and far between”.

Consistent with this focus on self-regulation, safe driving was linked to concepts of courtesy, manners and gentlemanly behaviour, while reckless driving was viewed as indicative of a flawed character. As Clark (1999, p.6) notes:

“Speed and ungentlemanly behaviour were observed to be the causes of crashes but were not proven to be so. In fact, the road safety debate suffered from ignorance, assumption and the emphasis placed on the association of safety with morality. Countermeasures were based on the beliefs and guesswork of individuals and represented a conservative response to new technology and a sympathetic attitude to traditional travellers – pedestrians, horse riders and passengers in horse-drawn vehicles.”

The response to road crashes during this period bore the hallmarks of Norton’s (2015) ‘Safety First’ paradigm and, similar to the USA, the number of crashes and related fatalities continued to rise in Australia as the number of motor vehicles increased. As an example, between 1922 and 1927, the number of road crashes in the state of Victoria increased from 1,014 to 5,587 while the number of fatal crashes rose from 16 to 24 (Victorian Parliamentary Debate from 17 October 1928, cited in Clark, 1999).

3.2 Government & institutional responses to road crashes following WWII

In the years following WWII there was a renewed effort to address road trauma. Indeed, despite the dip in road fatalities during the war, there were still 160,000 people killed or injured on Australian roads (between July 1939 and June 1946) compared with 96,000 people killed or injured as a result of the war (Clark, 1999). Growing community concern about road crashes was reflected in regular stories and editorials in newspapers and the journals of state motoring clubs in Australia (Clark, 1999).

A key institutional response to these concerns was the establishment of a National Road Safety Council in May 1947. The Council was a joint initiative of the Federal and State Transport Ministers and was funded by the allocation of 100,000 pounds from Federally collected petrol taxes (Adelaide News, 1947). As reported in the Adelaide News on 28 May 1947 (p.2):

“The high accident death roll [sic] shows how necessary it is to tackle road safety on a national basis. One of the most important functions of the Road Safety Council will be to prepare a national traffic code. . . The Road Safety Council’s plans include a publicity drive to educate the public in road traffic dangers. Individual States have tried to do this through their own road safety campaigns, but evidently the lesson has not gone deep enough.”

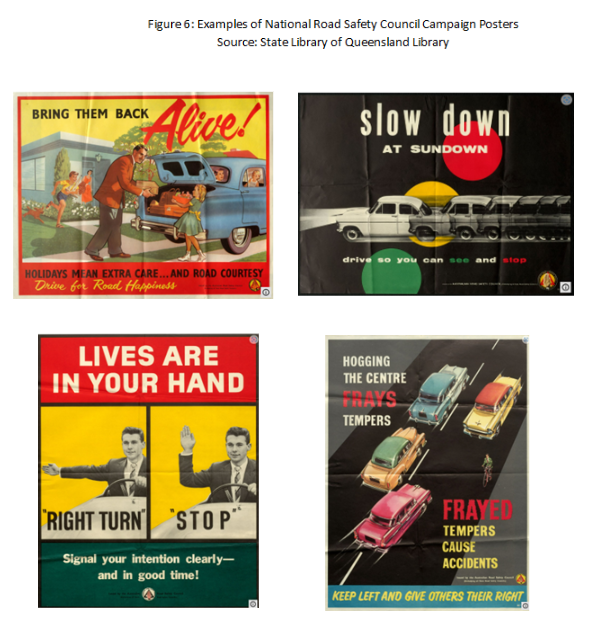

With the support of state-based councils, the National Road Safety Council promoted road safety messages through posters, songs, films, radio serials and speeches (Clark, 1999). As shown in the collage of posters in Figure 6, these campaigns mainly focused on exhorting drivers to be more responsible, cautious and courteous. As noted by Clark (1999, p.9), during this period:

“The promotion of road safety was a crusade, marked by failure, fervour and a certain tone of desperation. The road toll kept rising and the road safety authorities appeared to be making no headway and seemed bereft of inspiration.”

During the post-war period, state-based police forces were also central to road safety efforts. Consistent with Norton’s ‘Control’ paradigm, police prevention efforts focused on detecting reckless drivers, particularly those who drove after drinking alcohol or exceeded the speed limit. However, without the aid of modern technology, enforcement of these behaviours was difficult and subjective. Furthermore, efforts to promote traffic offenders as criminals was at odds with community perceptions, with many considering them unwary or unlucky (Clark, 1999).

As Australia entered the 1960s, concerns about the number of road fatalities and injuries intensified, reflecting the rapid motorisation that was occurring. There were growing calls for a more scientific approach to be taken, based on improved crash data collection and research. More action was demanded from the Federal Government and in 1961 the National Road Safety Council was reconstituted in an attempt to administer road safety more efficiently (Clark, 1999). Influential organisations began to question the strong emphasis on publicity campaigns, with the Australian Medical Association (AMA) arguing that “there is no real evidence that such propaganda has any significant effect on the accident rate” (AMA, 1968; cited in Clark, 1999, p.8). In 1969, the Royal Australasian College of Surgeons (RACs) established a national Road Trauma Committee (along with state-based Trauma Committees) to lobby for measures such as mandatory seatbelt wearing, alcohol limits and helmet laws (RACS, undated).

3.3 The influence of road safety developments in the USA and other countries

Calls for a new approach to road safety in Australia were fuelled by developments in other countries experiencing rapid motorisation, particularly the USA. Between 1961 and 1969, road fatalities in the USA soared from 38,091 to 55,791 (Trinca et al, 1988). Against this backdrop, a number of important developments occurred which had implications for road safety at the global level. In 1965, Ralph Nader’s groundbreaking book, Unsafe at Any Speed: The Designed-In Dangers of the American Automobile was published. The book criticised the US automobile industry for prioritising style over safety, thereby contributing to preventable crashes and related deaths and injuries. A key focus of the book was on the safety of the Chevrolet Corvair, manufactured by General Motors (GM). As reported by Trinca et al (1988), GM inadvertently contributed to the controversy surrounding their vehicle by hiring private detectives to trail Nader.

“When GM’s behaviour came to light, it made a hero of Nader, made his book Unsafe at Any Speed a best seller, made villains of GM in the eyes of some and gave Washington politicians an opportunity for chest thumping about protecting the public. The legislation, up to that point proceeding at a snail’s pace, was quickly passed creating the then National Highway Safety Bureau (NHSB), now the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) (Trinca et al, 1988, p.48).

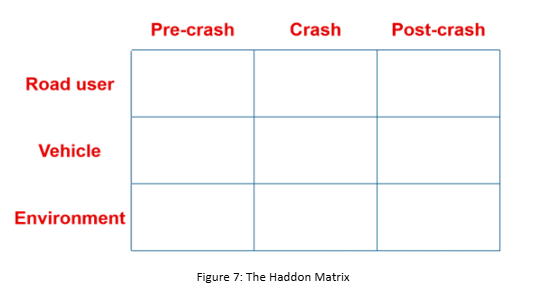

In another key development, William Haddon Jr was appointed the first Director of the NHSB. An epidemiologist by training, Haddon pioneered a more scientifically driven public health approach to road safety, which focused on injury control as well as crash prevention (Clark, 1999; ICORSI, undated). One of his major contributions was the creation of the Haddon Matrix, which provided a structured approach to conceptualising the breadth of factors contributing to road crashes and associated injuries, as well as the potential to intervene at different time points to prevent crashes and reduce injuries. While Haddon later expanded his matrix to include the social environment, the classic form of the matrix is shown in Figure 7. It differentiates between the influence of road environment, vehicle and road user related factors as determinants of road injuries, and the opportunity to intervene to reduce their influence at the pre-crash, crash and post-crash phase. Prior to this, the majority of crash prevention efforts had focused on modifying the behaviour of road users in the pre-crash phase through enforcement and education (consistent with Norton’s ‘Control’ paradigm). Haddon championed the need to better understand the complexity of the factors contributing to road crashes and related injuries, along with the need to identify and implement effective interventions at each of the three crash phases. In particular, his philosophy of ‘loss reduction’ focused attention on the need to make the road environment and vehicles more crashworthy (corresponding to Norton’s ‘Crashworthiness’ paradigm).

Two other international developments had a strong influence on road safety thinking in Australia during the 1960s. The first was the invention of the three-point safety belt by Volvo engineer Nils Bohlin in 1959, the patent for which was made freely available to other vehicle manufacturers and is credited with saving at least a million lives worldwide (Volvo Group, undated). The second was the invention of the Breathalyzer by Robert Borkenstein in the mid-1950s, which was the first commercially successful breath testing device that revolutionised the enforcement of drink driving laws globally (McClean, 2012; Jones, 2022).

3.4 The adoption of a ‘scientific approach’ to road safety in Australia

Consistent with international developments, the Federal and State Governments introduced a range of institutional and legislative initiatives in the late 1960s and 1970s that were designed to respond to the road trauma problem in a more scientific way. At the institutional level, specific agencies were established to oversee the development and evaluation of road safety countermeasures, including the: Australian Road Research Board (ARRB); Federal Office of Road Safety (FORS); NSW Traffic Accident Research Unit (TARU); and Victorian Road Safety and Traffic Authority (RoSTA). The activities of these organisations were characterised by: i) an epidemiological approach drawing on a range of disciplines, e.g., engineering & behavioural science; ii) a strong interest in the crashworthiness of vehicles, particularly seat belts; and iii) a growing concern about the role of alcohol in road crashes (Trinca et al, 1988; Clark, 1999).

Although the Australian Design Rules (ADRs) for motor vehicles had first been introduced in 1947, the growing focus on vehicle crashworthiness led to the adoption of the first five safety-related ADRs in 1967 covering reversing lights, door latches, seat anchorages and seat belts (Clark, 1999). This laid the groundwork for Victoria to become the first jurisdiction in the world to introduce the compulsory wearing of seat belts in 1970, closely followed by the other states (NRMA, 1988; Clark, 1999).

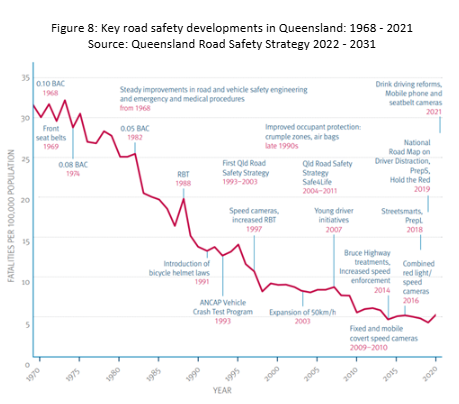

Over the following decades, the Australian jurisdictions either strengthened or introduced a range of innovative and world-leading safety laws relating to: motor vehicle occupant protection (including child restraints); motorcycle rider safety (e.g. compulsory helmets); legal blood alcohol limits; breath testing (including random breath testing); driver licensing (including demerit points and restrictions on provisional/probationary drivers, which culminated in graduated driver licensing systems); traffic control (including roundabouts and pedestrian crossings); speed management; and automatic camera enforcement for red light running and speed cameras (McLean, 2012; NRMA, 1988). Figure 8 identifies when many of these key road safety countermeasures were introduced within the context of one Australian state (Queensland). As noted in Figure 8, these countermeasures were complemented by ‘steady improvements in road and vehicle engineering and emergency and medical procedures’. A more detailed discussion of these improvements is provided in the various chapters within the Prevention & Intervention section of the BoK.

As shown in Figures 5 and 8, the introduction of this more scientific approach to road safety was reflected in the dramatic fall in road deaths from the early 1970s into the 1990s. Much of the early success during the period was attributed to improvements in driver and rider protection, with Michael Henderson (the first Director of TARU) arguing that the introduction of compulsory seat belt and motorcycle helmet wearing had “resulted in a more dramatic reduction in deaths than has ever been achieved before” (Henderson, 1972, cited in Clark, 1999, p.14).

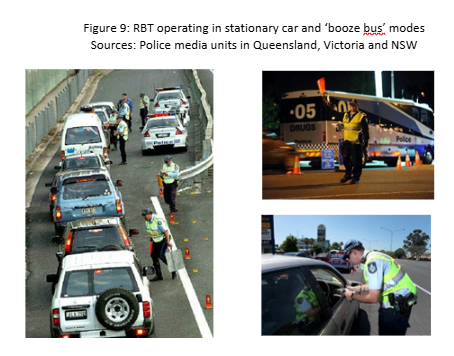

The other important innovation during the period that attracted worldwide attention was the introduction of random breath testing (RBT), which was a “high point in the story of Australian road safety” (Clark, 14, p.14). Historically, the police in Australia (as is still the case in many other countries) were required to have a reason to stop and breath test a driver, such as observing signs of intoxication or in the event of a crash (which is often referred to as ‘probable cause’ within the US context). However, the legislation underpinning RBT gave police the power to breath test drivers at any time or place, irrespective of their behaviour (Homel, 1990). Although Victoria was the first jurisdiction to introduce RBT in 1976, it was the intensive ‘boots and all’ approach adopted in New South Wales in 1982 that set the model for other states to follow (Homel, 1988; Homel, 1990; Homel, 1993; Job, 1999; Watson, Mitchell & Fraine, 1994). The key goal of RBT was to deter drink driving by increasing drivers’ perceived risk of apprehension. Central to this was the use of highly visible police operations, including the use of ‘booze buses’, to undertake large scale testing of drivers (see Figure 9), supported by intensive mass media public education.

An evaluation of the NSW program showed an immediate 36% reduction in alcohol-related fatalities and serious injuries, and an overall reduction of 22% in fatal crashes, which was sustained for at least five years (Homel, Carseldine & Kearns, 1987; Homel, 1990). Other research in NSW confirmed that following the introduction of RBT there were changes in moral and social attitudes to drink driving and increased social disapproval of the behaviour (Job, 1999). While subsequent evaluations confirmed the effectiveness of RBT, its long-term success appeared to be linked to sustained high levels of testing and innovation (Cavallo & Cameron, 1992; Watson et al, 1994; Henstridge et al, 1997). Further information about RBT can be found in the Behavioural Interventions chapter.

3.5 The increasing focus on road safety strategies

While the Australian states and territories continued to introduce new countermeasures during the 1990s, the rate of decline in road fatalities had begun to slow (see Figure 5). In response, there was growing recognition that a more strategic approach to road safety was required that would prioritise key initiatives and coordinate efforts of all stakeholders involved in their delivery. Australia’s first 10-year National Road Safety Strategy was released in 1992. It was a cooperative effort of the Federal, State and Territory Transport Ministers and included an objective to reduce the annual road fatality rate from 12 to 10 deaths per 100,000 people by the year 2001 (FORS, undated; ATC, 2000). Soon after this, each of the States and Territories released a road safety strategy focusing on jurisdiction-specific responsibilities, priorities and stakeholder engagement. While the role of these strategies was to coordinate road safety efforts at the local level, their overall goals, objectives and targets typically aligned with the National Road Safety Strategy (Watson, 2019).

Over the following years, the Australian Federal, State and Territory Governments continued to release longer-term road safety strategies (typically for 10-year periods), supported by shorter-term action plans (see Figure 10 for the national strategies and a selection of the action plans). The 2nd National Road Safety Strategy, released in 2001, included a target to reduce fatalities by 40% relative to population, which equated to a reduction from 9.3 deaths per 100,000 people to no more than 5.6 deaths per 100,000 (ATC, 2000). While significant gains were made during the 10-year period, only a 34% reduction in fatalities was achieved (ATC, 2011; Watson, 2019).

The 3rd National Road Safety Strategy released in 2011 was underpinned for the first time by the Safe System Approach (which is discussed further in the next section). It included a 30% fatality reduction target, expressed in absolute rather than per population terms. For the first time, a target for reducing serious injuries was included, which was also 30% (ATC, 2011). By the mid-point of this 3rd strategy, however, trends in the data were indicating that neither target was on track to be achieved. In response to stakeholder concerns, the Federal Government established an independent inquiry into the strategy, which resulted in 12 recommendations including the need for: greater national leadership and funding of road safety; the adoption of a zero road deaths target for 2050, with interim targets; the adoption and commitment to key performance indicators; and a review of national road safety governance processes (Woolley et al, 2018). In response, the Federal Government led a Review of National Road Safety Governance, which concluded: “There is a clear need for greater leadership, strengthened management, heightened accountability and more effective coordination to reduce road trauma across Australia” (DITCRD, 2019, p. 3). By the end of 2020, only a 22.4% reduction in road deaths had been achieved against the agreed baseline for the 3rd strategy (AAA, 2021). Furthermore, while no direct means of measuring serious injuries was yet available, the trend in severe injuries appeared to be plateauing.

Despite previous targets not being achieved, the 4th National Road Safety Strategy released in 2021 included the relatively ambitious targets to reduce the annual number of fatalities by at least 50 % and serious injuries by at least 30% by 2030 (ITM, 2021). The strategy continued to be underpinned by the Safe System Approach, although it adopted a social model approach to foster a positive road safety culture across society. As at the end of 2023, the “data indicate no jurisdiction or road user group is on track to achieve any of the National Road Safety Strategy headline targets by 2030” (AAA, 2024, p.4).

3.6 The emergence of the Safe System Approach

While the Safe System Approach underpinned the 3rd National Road Safety Strategy, it first appeared in the National Road Safety Action Plan 2003 and 2004 (ATC, 2003). The development of the Safe System Approach in Australia was strongly influenced by two strategic frameworks that emerged from Europe in the 1990s (Wegman, 2016; Watson, 2019; Corben, Peiris & Mishra, 2022). The first of these was Sweden’s Vision Zero, which was adopted by the Swedish Government in 1997. At its core was the ethical principle that no one should be killed or seriously injured on the road system (Tingvall, 1998). Moreover, at a political level, it was argued that road travel should be as safe as other forms transport. As such, the long-term goal of Vision Zero became the elimination of death and serious injury on the Swedish road system. The strategic principles underpinning Vision Zero included the need for the traffic system to better adapt to the needs, mistakes and vulnerabilities of road users and to reflect the tolerances of the human body to injury. In a major departure from traditional road safety thinking, it was acknowledged that while road users are responsible for complying with road rules, system designers are responsible for overall safety performance of the system (Tingvall, 1998; Vagverket, 2001). The second strategic framework that influenced the development of the Safety System Approach was Sustainable Safety, which was developed in early 1990s in the Netherlands and formally adopted in 1996. The long-term goal of this approach was to create a sustainably-safe traffic system that, firstly, limits the chances of crashes occurring and, secondly, reduces the chances of serious injury in the event of a crash (van Schagen & Janssen, 2000). Whereas the focus of Vision Zero was on minimising the harmful outcomes of road crashes, Sustainable Safety aimed to optimise the interactions between road users, vehicles and the road system to reduce the incidence and severity of crashes (Watson, 2016a).

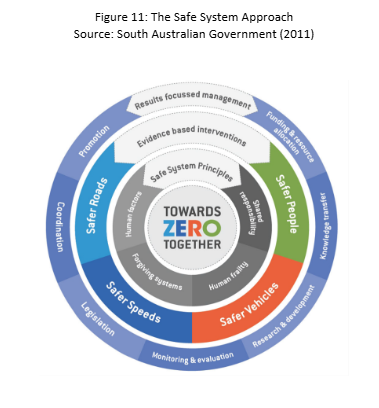

The Safe System Approach originally emerged in Australia but gained international attention when it was incorporated into the International Transport Forum’s 2010 report Towards Zero: Ambitious Road Safety Targets and the Safe System Approach (ITF, 2010). Shortly after, it was included as the key strategic framework underpinning the Global Plan for the 1st Decade of Action for Road Safety (UNRSC, undated). As articulated in a later ITF report, the strategic principles underpinning the Safe System Approach are:

- Humans inevitably make mistakes that can result in road crashes

- The human body has physical limits, in terms of the forces it can tolerate

- The responsibility for the safety of the system needs to be shared by all those involved in the design, building and management of the system, as well as road users

- A holistic approach is required to managing the system to build in redundancy and thereby optimise the safety of road users (ITF, 2016)

While the Safe System Approach has been depicted in a variety of ways, Figure 11 highlights two important implementation considerations. Rather than be implemented in isolation, the Safe System Approach should ideally be supported by evidence-based interventions and be embedded within an overall management system (South Australian Government, 2011).

The Safe System Approach has been widely adopted around the world but is not without its critics. For example, it has been criticised for: i) not capturing the influence of broader sociocultural influences on road user behaviour (Johnston, 2010); ii) not being sufficiently informed by systems thinking (e.g. Salmon & Lenné, 2014); tolerating the influence of human error on road safety, thus missing opportunities for prevention (Williamson, 2021); and iv) being overly focused on HICs, with limited applications in LMICs (Watson, 2016b). As such, it has been argued that the Safe System Approach needs to continue to evolve to better reflect advances in systems thinking and the safety management systems used in other fields (e.g., ACRS, 2024).

3.7 Evolution of stakeholder roles and responsibilities

Since the 1980s, the institutions and stakeholders involved in Australian road safety have continued to evolve. A detailed discussion of the relevant organisations and their contributions is beyond the scope of this case study. However, some key themes are identified below.

National leadership of road safety

As noted in section 3.4, a key institutional development in the early 1970s was the establishment of a traffic safety unit within the Federal Department of Transport, which became known as the Federal Office of Road Safety (FORS) (Trinca et al, 1988). Until the late 1990s, FORS played a key role in Australian road safety by leading improvements in vehicle safety regulation, collecting and disseminating national road crash statistics, coordinating national road safety efforts, funding research activities, and undertaking educational campaigns (Trinca, et al, 1988; Clarke, 1999; Woolley et al, 2018). In July 1999, however, FORS was absorbed into the newly created Australian Transport Safety Bureau (ATSB), which also had responsibly for air and marine safety incident investigations. In March 2008, responsibility for road safety passed to the Road Safety Branch within the Federal Department of Transport (Woolley et al, 2018).

As reported in the 2018 National Inquiry into the National Road Safety Strategy (NRSS), the discontinuation of FORS was associated with a decline in national road safety leadership:

“. . . previous policy leadership either through FORS or ATSB is no longer obvious. It could be argued that this lack of leadership since 1998 has contributed to a lessening decline in national road safety performance, and the recent increase in road trauma as the longer term benefits of that leadership have “worn off”. Short term perspectives and limited long term strategic thinking on the safety issues dominate, and are still almost always in the context of mobility” (Woolley et al, 2018, p. 28).

To some degree, the void in national leadership was filled by Austroads and its Road Safety Task Force (Woolley, et al, 2018). Among its activities, this task force coordinates research that: supports the incorporation of Safe System principles and practices into Austroads Guides and other documents; supports the current Australian and New Zealand road safety strategies; and investigates emerging road safety issues (see Safety Task Force and Projects | Austroads). However, Austroads has no responsibility for resources or their delivery, nor accountability for road safety outcomes. Consequently, one of the recommendations arising from the National Inquiry into the NRSS was to: “Establish a national road safety entity reporting to the Cabinet minister with responsibility for road safety” (Wooley et al, 2018, p.35).

The role of Parliamentary Committees

A key feature of the Australian political system is the use of Parliamentary Committees, at both the Federal and State level, to investigate issues of concern and recommend actions for improvement. These committees typically have members drawn from the various political parties represented in the Parliament and have significant inquiry powers. Over the years, Federal and State road safety committees have made important contributions to road safety by drawing attention to emerging issues and recommending the introduction of new countermeasures (Hansen & Bates, 2004). Most notably, the Parliamentary Road Safety Committee in NSW, known as STAYSAFE, recommended the introduction of RBT (Homel, 1993), as well as many other road safety reforms (Hansen & Bates, 2004). In Queensland, the Parliamentary Travelsafe Committee, which operated between May 1990 and February 2009, recommended the introduction of many key initiatives including: a lower urban speed limit, speed cameras, graduated driver licensing, and vehicle impoundment for drink drivers (Watson, 2024).

The role of non-government organisations

Many non-government organisations have also made a notable contribution to road safety in Australia. As noted by Clark (1999), the Australian Automobile Association (AAA) and the various state motoring clubs played an important role in the first half of the 20th century by drawing attention to deficiencies in the road network and the escalating number of road deaths and injuries. In the latter half of the century, many of the clubs expanded their road safety activities to complement their advocacy role, including the delivery of various education programs. In 2014, AAA commenced its ongoing benchmarking of road safety performance (see AAA, undated). This benchmarking contributed to growing concerns among road safety stakeholders about the failure of the 3rd National Road Safety Strategy to achieve its targets, which in turn contributed to the establishment of the Independent Inquiry into the NRSS (Watson, 2019).

The motoring clubs also contributed to the establishment of two influential independent road safety organisations, which have strong international affiliations. The first of these is the Australasian New Car Assessment Program (ANCAP), established in 1993 to provide independent advice to consumers about the safety performance of passenger cars. ANCAP’s membership is drawn from both Australia and New Zealand and includes the motoring clubs and various Federal and State Government road safety agencies. ANCAP conducts crash tests and performance assessments of cars focusing on their safety features and technologies, in order to provide consumers with a star-based rating of relative safety performance. ANCAP is one of ten New Car Assessment Programs (NCAPs) operating around the world (ANCAP, undated). The second independent organisation with historical links to the motoring clubs is the Australian Road Assessment Program (AusRAP). AusRAP is the Australian version of the International Road Assessment Program (iRAP), which uses a suite of tools to assist governments to maximise the safety of their road networks. These tools include Star Ratings, Risk Maps and Safer Roads Investment Plan (iRAP, undated). AusRAP was introduced into Australia by the AAA in 2000, but responsibility for its management was transferred to Austroads in 2021 (Austroads, undated).

At a professional level, the key organisation representing road safety researchers and practitioners in Australia and New Zealand is the Australasian College of Road Safety (ACRS). The ACRS was established in 1988 at the 2nd Biennial National Traffic Education Conference to provide a permanent professional network for those working in the road safety field (Clark, 1999). The ACRS has historically engaged in a range of activities including: road safety advocacy; convening state-based chapters; preparation of submission to government; preparation and dissemination of policy position statements on a range of topics; hosting national and state level conferences, seminars and forums; and publishing a road safety journal, now referred to as the Journal of Road Safety (ACRS, undated). In 2015, the ACRS became the co-host (along with Austroads) of the annual Australasian Road Safety Conference. This event amalgamated the previous annual Australasian Road Safety Research, Policing & Education Conference with the ACRS’s own biennial conference to establish one of the largest road safety conferences of its type in the world. More recently, the ACRS has led the development of the Road Safety Body of Knowledge (BOK).

Road safety research capacity & coordination

Australia has a rich history of undertaking and disseminating road safety research. In 1960, the Australian Road Research Board (ARRB) was established with funding from the National Association of Australian State Road Authorities (NAASRA) (which later became Austroads) (Trinca et al, 1988; Sharp et al, 2011). ARRB’s original focus was primarily on the field of road engineering. However, in 1962 it funded an in-depth study into urban road crashes in South Australia, as well as a similar study in Queensland (Trinca et al, 1988). This commenced a long history of research into road safety, which still continues (Sharp et al, 2011).

As noted in section 3.4, during the late 1960s and early 1970s various government road safety agencies were established including the Federal Office of Road Safety (FORS); NSW Traffic Accident Research Unit (TARU); and Victorian Road Safety and Traffic Authority (RoSTA) (Clark, 1999). These agencies typically conducted research in-house, involving multidisciplinary teams of researchers. One exception to these government-based research groups was the Road Accident Research Unit (RARU), which was established at the University of Adelaide in 1973 under the leadership of Jack McLean (NHMRC, undated). Between 1981 and 1998, RARU was funded by the National Health & Medical Research Council (NHMRC) and pioneered research into a wide range of road safety issues including drink driving and speeding. RARU was subsequently renamed the Centre for Automotive Safety Research (CASR) and celebrated its 50th anniversary in 2023 (CASR, undated).

The shift in research expertise from government agencies to university centres was further reinforced in the 1980s and 1990s, with the establishment of the Monash University Accident Research Centre (MUARC – https://www.monash.edu/muarc) in 1987 and the Centre for Accident Research & Road Safety – Queensland (CARRS-Q) in 1996 at the Queensland University of Technology (now known as the MAIC-QUT Road Safety Research Collaboration – https://research.qut.edu.au/mqcollab/). MUARC is currently also the host of the National Road Safety Research Program (NRSPP, – NRSPP Australia – Home), which is a collaborative network designed to assist organisations implement effective road safety strategies in the workplace. Later, road safety research groups were established at the University of NSW (TARS – https://www.unsw.edu.au/science/our-schools/aviation/our-research/transport-and-road-safety-tars-research-centre) and, most recently, at the University of Western Australia (WACRSR – https://www.uwa.edu.au/projects/centre-for-road-safety-research/wacrsr-site-link).

During the 1980s and 1990s, FORS played an active coordination role for road safety research in Australia, which included convening the Research Coordination Advisory Group (RCAG) and contributing to the development of a National Road Safety Research & Development Strategy in 1993 and its update in 1997 (ACRS, 2013a). However, with the dissolution of FORS, a gap began to emerge in road safety research coordination processes. This prompted the ACRS to work with the NHMRC to develop a National Road Safety Research Framework in 2013 (ACRS, 2013b). However, this framework gained little traction with key stakeholders.

The need for more effective processes for coordinating road safety research in Australia was recognised in the Independent Inquiry into the NRSS (Woolley et al, 2018) and, most recently, in the National Road Safety Action Plan 2023 -2025. One of the actions included in the plan was:

“Work with states and territories and road safety national agencies to develop a National Road Safety Research Framework to co-ordinate and prioritise road safety research (ITM, 2023, p.13).

At the time of writing this chapter (mid-2025), progress on this action remained unknown.

3.8 Where is Australia now?

As shown in Figure 5, the annual number of road deaths in Australia has been increasing over recent years. Moreover, as noted section 3.5, as at the end of 2023, none of the Australian jurisdictions were on track to achieve any of the key targets in the current National Road Safety Strategy (AAA, 2024). As such, it appears that Australia is facing some major challenges to reverse the current trend in road deaths and meet the targets in its current road safety strategy.

There is a lack of definitive evidence explaining current road trauma trends in Australia. It is possible that it may reflect a failure to adequately address the underlying structural, institutional and funding problems identified in the Independent Inquiry into the NRSS (Woolley et al,2018). Additionally, a range of other factors have recently been cited in the literature and the media to account for the recent increase in road trauma including:

- the increase in risky driving behaviour associated with the COVID-19 pandemic, both during the lockdowns and afterwards among some drivers (e.g. Watson-Brown et al, 2021; Catchpole & Naznin, 2020; Watson-Brown et al, forthcoming);

- changes in the make-up of the vehicle fleet, particularly the increase in sales of large SUVs (sometimes referred to as the ‘truckification’ of the fleet) (SMH, 2023; Cosmos, 2025);

- the growth in active transport and micromobility, including the increasing use of e-scooters in some cities (e.g. iMove, undated; Schramm & Haworth, 2023; We Ride Australia, 2023);

- the diversion of police resources previously dedicated to road policing to deal with other social issues of concern, such as domestic violence; and

- the influence of broader societal factors impacting on road use, including the growth in online shopping and home delivery services (e.g. Oviedo-Trespalacios, Rubie & Haworth,2022).

Many of these issues are discussed in more detail in later chapters of the BoK. While further research into these issues may assist, it is apparent that Australia is facing major challenges to reverse current increasing trends in road trauma.

4. Emergence of the global road trauma crisis

As noted earlier, concerns about the road safety situation in LMICs began to emerge during the 1990s. This reflected the rapid motorisation that was taking place in these countries and the associated escalation in road deaths and injuries. One of the first global-level reports to give attention to the issue was the International Federation of the Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies’ World Disaster Report (IFRC, 1998). This report was one of the first to identify road trauma as a humanitarian crisis requiring a global response (Watson, 2016). The interactive timeline below identifies the key developments that have shaped the subsequent global response to this crisis. Following this, some of the key themes emerging from this timeline are discussed.

INTERACTIVE TIMELINE HERE

4.1 The key role of data

The first comprehensive overview of the global road safety situation was provided in the World Report on Road Traffic Injury Prevention, which was jointly issued by the World Health Organization (WHO) and the World Bank in 2004. While the report acknowledged the limitations inherent in road crash data collection and reporting systems of many countries, it estimated that there were 1.2 million people being killed in road crashes each year and as many as 50 million being injured (WHO, 2004). Moreover, it was projected that road trauma would increase by about 65% over the next 20 years unless action was taken. By demonstrating the scale of the global road safety crisis, the report made a “powerful case for concerted and urgent action to address the problem, as a global development priority” (World Bank, undated). Over the following two decades, the WHO released five Global Status Reports on Road Safety, which have served as an important means to monitor trends in global road trauma, benchmark country-level responses to the problem, evaluate gaps in data and interventions, and stimulate research on road safety (Segui-Gomez et al, 2025). The key findings from the most recent Global Status Report are outlined in the following chapter, which provides an up-to-date overview of the global road safety crisis.

4.2 The leadership provided by global institutions

A key enabler of global-level responses to road trauma was the leadership provided by international institutions. The first UNGA resolution on global road safety came in 2003, which “called on governments and civil society to raise awareness for, promulgate, and enforce appropriate laws” (Hyder et al, 2021). This was followed by a series of resolutions that were designed to motivate UN member countries to allocate greater resources to road crash prevention and adopt good practice approaches to road safety. It was through these resolutions that both the 1st and 2nd Decades of Action for Road Safety were proclaimed, to heighten the visibility of the problem and build momentum towards the achievement of ambitious fatality reduction targets.

The groundwork for the first UNGA resolution had been laid by the WHO, which commenced a five-year strategy on global road safety in 2001 (Hyder et al, 2021). As noted above, the WHO then released the World Report on Road Traffic Injury Prevention in 2004. In recognition of the leadership role being played by the WHO, UNGA invited it to work with the UN regional commissions, to become the coordinator for road safety issues across the UN system. In addition, the WHO was invited to become the Secretariat for a new entity called the United Nations Road Safety Collaboration (UNRSC), which was designed to facilitate cooperation among the diverse range of organisations involved in road safety and strengthen implementation of the UNGA resolutions (WHO, undated). Since that time, the WHO has undertaken a range of activities to promote good practice road safety at the global, regional and country level. Besides convening the UNRSC and producing the Global Road Safety Status Reports, the WHO has played a key role in coordinating the four Global Ministerial Conferences and seven UN Global Road Safety Weeks held to date.

As noted above, the IFRC was one of the first global organizations to recognise road trauma as a humanitarian crisis. In 1999, the IFRC collaborated with the World Bank and the United Kingdom’s Department for International Development (DFID) to establish the Global Road Safety Partnership (GRSP), with the goal of creating partnerships between government, private sector and civil society to build road safety capacity in LMICs (see https://www.grsproadsafety.org/). Many other international organizations have also contributed to global road safety efforts as identified in the interactive timeline.

4.3 The role of philanthropic and corporate funding

A key feature of global road safety efforts in the 21st century has been the support provided from philanthropic and corporate donors. Leading the way in philanthropic funding was Bloomberg Philanthropies, which first piloted a road safety intervention program in Cambodia, Vietnam, and Mexico in 2007. This evolved into the Bloomberg Philanthropies Initiative for Global Road Safety (BIGRS), which was a multi-country program that aimed to reduce road crash fatalities and injuries in low-and middle-income cities and countries. To date, there has been three phases of the BIGRS covering the periods 2010 – 2014, 2015 – 2019 and 2020 – 2025. To demonstrate the scale of this initiative, the third phase (2020 – 2025) involved the investment of $240 million to enhance road safety in 15 countries and 27 cities. Since 2007, Bloomberg Philanthropies has invested $500 million into enhancing road safety in LMICs (Bloomberg, undated). An evaluation of the Bloomberg Philanthropies funded activities for the period 2007 to 2018, estimated that it had resulted in the saving of 97,148 lives up until 2018, with a further 214,608 lives projected to be saved up until 2030 (Hendrie, Lyle & Cameron 2021).

The private sector has also contributed to global road safety efforts through a variety of mechanisms. In 2006, a group of seven companies (Ford, GM, Honda, Michelin, Renault, Shell and Toyota) came together under the auspices of GRSP to establish the Global Road Safety Initiative (GRSI). In the largest-ever single private sector investment in road safety at the time, it funded a five-year, US$10 million program to create and implement demonstration projects in South-East Asia, China and Brazil (GRSP ref). In 2018, the United Nations Road Safety Fund was launched to boost road safety worldwide and support countries in achieving the road safety-related SDGs. Among the initial funders was the FIA Foundation, which donated $10 million (Hyder et al, 2021). Overall, private sector organisations have comprised 74% of the donors to the fund (UNECE, undated).

While philanthropic and corporate donors are an important source of catalytic funding, many countries continue to underinvest in road safety. As discussed in the following chapter, many countries have come to rely on philanthropic funding and failed to integrate road safety investment into existing road and traffic management budgets.

4.4 Framing of road safety as a global development issue

From the time the World Report on Road Traffic Injury Prevention was released in 2004, there was a recognition that road trauma warranted being treated as a global development priority. However, a constraining factor was that the UN’s Millenium Development Goals, which guided international development efforts between 2000 and 2015, did not address road safety. As a consequence, there was a concerted effort within the global road safety community to ensure that the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) (which were to guide development up until 2030) addressed the issue. As discussed in more detail in the following chapter, two road safety specific goals were subsequently included in the SDGs, thereby providing an important impetus for global road safety.

4.5 The importance of capacity building

Historically, there has been a scarcity of trained human resources in many LMICs due to the underinvestment in road safety (Hyder et al, 2021). While some roles can be performed by ‘outside experts’, sustainable improvements in road safety require local expertise. As a consequence, many of the activities funded through initiatives like the Bloomberg Initiative for Global Road Safety, the Botnar Child Road Safety Challenge, and the United Nations Road Safety Fund have been designed to build technical capacity within LMICs. A recent evaluation of the technical assistance provided through the BIGRS concluded that it:

“. . . can improve road safety capabilities and increase the uptake of evidence-informed interventions. Hands-on capacity building tailored to specific implementation needs improved implementers’ understanding of new approaches. BIGRS generated novel, city-specific analytics that shifted the focus toward vulnerable road users. BIGRS and city officials launched pilots that brought evidence-informed approaches. This built confidence by demonstrating successful implementation and allowing government officials to gauge public perception” (Neill et al, 2024, p.1).

5. Conclusion

5.1 Where are we now, half way through the 2nd Decade of Action for Road Safety?

As demonstrated in this chapter, the history of road safety has followed two main paths. The first path involved HICs that were early adopters of the motor vehicle. These countries experienced a gradual increase in road trauma up until the 1950s and 1960s, at which time there was a major escalation in the scale of the problem due to rapid motorisation. Fortunately, during the 1970s and 1980s a more scientific approach emerged that was informed by public health principles. This led to a stronger focus on understanding the complexity of the factors contributing to road crashes and to the implementation of countermeasures designed to both prevent crashes and reduce their severity. As a result, many HICs experienced dramatic reductions in road deaths during the 1970s and 1980s. However, the rate of decline began to slow in the 1990s, prompting countries to adopt strategic frameworks like Vision Zero and the Safe System Approach to better direct and coordinate road safety efforts. While improvements continued into the 21st century, road deaths and serious injuries have more recently either plateaued or started to rise again in some HICs. The in-depth case study of the Australian situation suggests that its recent increase in road deaths is due to underlying structural, institutional and funding problems (see Woolley et al, 2018), as well as to some fundamental changes in road use brought about by broader societal changes including the impact of COVID-19.

The second path in the history of road safety has been that followed by LMICs. In general, these countries only started to experience the problems associated with rapid motorisation towards the end of the 20th century. The ensuring global road trauma crisis has attracted considerable attention from key international institutions and support from philanthropic and corporate sources. However, the level of investment in road safety has not been commensurate with the harm caused by road crashes nor the ‘rhetoric’ associated with the issue (Hyder et al, 2021). In particular, many LMICs continue to underinvest in road safety and fail to truly value the benefits of improved safety (Hyder, et al, 2021). Not surprisingly, the data collected via the Global Status Reports on Road Safety suggests that global road deaths continued to rise to an estimated 1.35 million in 2016. As discussed in the next chapter, it now appears that global road deaths may have peaked, but the situation is complicated by the impacts of COVID-19 on road use. However, there are some encouraging signs beginning to emerge that global road safety efforts are bringing about positive changes. A recent evaluation conducted by the WHO using data from the Global Status Reports found that there has been steady growth in the number of country-level road safety lead agencies, strategies and quantified fatality reduction targets during the period 2009-2023 (Belin, Khayesi & Tran, 2025). Another recent study using data from the same source found a downward trend in the rate of road deaths in 16 middle- and high-income countries (MHICs) during the period 1990–2021 (Khayesi & Iaych, 2025). The authors suggested that this downward trend represents a second wave of fatality reductions, similar to the first wave that occurred in other HICs during the 1970s. Despite these positive signs, considerable challenges remain in further stabilising the road safety situation in many LMICs and ensuring a sustained reduction in global road trauma.

5.2 Lessons to be learnt from the history of road safety

Writing in 1988, Trinca et al provided the following overview of the lessons that could be learnt from the history of road safety at that time. They contended that the key lessons were:

- Rationality – road safety is amenable to rational, cause and effect analysis;

- Limited objectives – there is no one panacea to the problem of road crashes, so there is a need to bring as many problems as possible under control, rather than try to prevent all crashes;

- Systems approach – a system-wide approach is required, achieved through co-operation and integration;

- Cost effectiveness – rational decision-making is critical to select between competing programs and priorities; and

- Pilot testing and evaluation – is required to ensure the wisest use of scarce resources.

Arguably, all of these lessons are equally as valid now as they were in 1988. However, Trinca et al (1988) were writing at a time when HICs were still experiencing the strong declines in road deaths associated with the adoption of the scientific approach to road safety. More recently, however, new challenges have emerged in both HICs and LMICs that suggest further learning is required.

The Australian case study presented above suggests that some HICs are experiencing societal changes that are impacting on road use in unexpected ways including: the growth in active transport and micromobility; changes in the make-up of the vehicle fleet; residual effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on road user behaviour; demands on Police resources that are impacting on road policing resources; and the growth in online shopping and home delivery services. This suggests that another lesson that needs to be learnt from more recent history is the need for:

- Adaptiveness – to identify and adapt to societal changes impacting on road use that have impacts on road trauma patterns

One of the key features of road safety in LMICs is the way that road trauma disproportionally impacts on the disadvantaged. As discussed further in the following chapter, those killed and injured in LMICs: represent 90% of global road deaths despite these countries having only 48% of the world’s registered vehicles; are more likely to be from lower socioeconomic backgrounds; and are more likely to be riding powered two- and-three-wheelers or be pedestrians, rather than car drivers. Moreover, road crashes are the leading cause of death globally for children and young adults aged 5–29 years. Together, these statistics suggest that the selection of road safety programs should not be based solely on the grounds of cost-effectiveness. Consideration needs to be given to the extent to which competing programs and priorities address the road safety needs of those most disadvantaged by road crashes. Unless this occurs, road safety efforts may simply reinforce existing inequities. Accordingly, a final lesson from the history of road safety requiring consideration is:

- Equity – the development and implementation of road safety programs should attempt to reduce existing inequities in the way road trauma impacts on disadvantaged groups of road users within societies.

6. References

AAA (undated). Benchmarking the National Road Safety Strategy. (Access on 23 July 2025 at: https://www.aaa.asn.au/publication/benchmarking-the-performance-of-the-nrss/)

AAA (2021). Benchmarking the Performance of the National Road Safety Strategy 2011 – 2020. Final Report. Canberra, Australia: Automobile Association of Australia (AAA). (Accessed on 14 July 2025 at: https://www.aaa.asn.au/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/AAA_QBR_Dec_2020_Final-web-1.pdf)

AAA (2024). Benchmarking the Performance of the National Road Safety Strategy. December 2023. Canberra, Australia: Automobile Association of Australia (AAA). (Accessed on 14 July 2025 at: https://www.aaa.asn.au/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/AAA_QBR_December_2023_web-1.pdf)

ACRS (2013a). Workshop to discuss the National Road Safety Research Strategy. Report on a workshop of the National Health and Medical Research Council and the Australasian College of Road Safety, Canberra, 21 & 22 February 2013. (Accessed on 24 July 2025 at: https://acrs.org.au/wp-content/uploads/RS-Workshop-Report-v.03-25-March-Preliminary-Report.pdf)

ACRS (2013b). National Road Safety Research Framework. (Accessed on 23 July 2025 at: https://acrs.org.au/wp-content/uploads/National-Road-Safety-Research-Framework.pdf#:~:text=This%20National%20Road%20Safety%20Research%20Framework%20%28the%20Framework%29,lowest%20rates%20of%20road%20trauma%20in%20the%20world)

ACRS (2024). ACRS Policy Position Statement: A New Systems Thinking Approach to Road Safety. Canberra, Australia: The Australasian College of Road Safety (ACRS). (Accessed online on 21 July 2025 at: https://acrs.org.au/wp-content/uploads/ACRS-Policy-Position-Statement_New-Systems-Thinking.pdf)

ACRS (undated). What we do. (Accessed on 23 July 2025 at: https://acrs.org.au/about/what-we-do/)

ANCAP (undated). About ANCAP. (Accessed online on 23 July 2025 at: https://www.ancap.com.au/about-ancap)

Adelaide News (1947). Increasing Road Safety, Adelaide News, 28 May 1947, p.2 (Retrieved from Trove on 4 July 2025 at: https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/127300446)

ATC (2000). National road safety strategy: 2001-2010. Canberra, Australia: Australian Transport Council (ATC), Australian Transport Safety Bureau.

ATC (2011). National road safety strategy: 2011-2020. Canberra, Australia: Australian Transport Council (ATC). (Accessed on 14 July 2025 at: http://www.atcouncil.gov.au/documents/files/NRSS_2011_2020_20May11.pdf)

Austroads (undated). About AusRAP. (Accessed on 23 July 2025 at: https://austroads.gov.au/safety-and-design/road-safety/ausrap)

Automotive History (undated). (Photo accessed on 21 July 2025 at: https://automotivehistory.org/may-26-1927-the-15-millionth-ford-model-t/

Belin, M., Khayesi, M. & Tran, N. (2025). ‘Road safety is no accident’: building efficient road

safety lead agencies, strategies and targets in the world, 2009–2023. Injury Prevention (Epub ahead of print accessed on 26 January 2025 at: https://injuryprevention.bmj.com/content/injuryprev/early/2025/07/15/ip-2024-045601.full.pdf)

BITRE (2010). Road Deaths in Australia 1925 – 2008: Information Sheet 38. Canberra, Australia: Bureau of Infrastructure and Transport Research Economics (BITRE), Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development and Local Government. (Accessed on 14 July 2025 at: https://www.bitre.gov.au/publications/2010/is_038)

BITRE (Undated). Road Deaths Australia—Monthly Bulletins. Canberra, Australia: Bureau of Infrastructure and Transport Research Economics (BITRE), Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development and Local Government.

Bloomberg (undated). Improving Road Safety. (Accessed on 25 July 2025 at: https://www.bloomberg.org/public-health/improving-road-safety/)

Bourne, E. (2025). The First Car Accidents in History and Their Lasting Impact. (Accessed on 2 July 2025 at: https://www.bourne.law/blog/first-car-accident/)

CASR (undated). CASR celebrates 50 years of making a difference. (Accessed on 23 July 2025 at: https://set.adelaide.edu.au/centre-for-automotive-safety-research/node/83)

Catchpole, J., & Naznin, F. (2020). Impact of COVID-19 on road crashes in Australia. Report prepared by the Australian Road Research Board for ADVI. Sydney, Australia: Australian and New Zealand Driverless Vehicle Initiative (ADVI). (Accessed on 24 July 2025 at:

Cavallo, A. & Cameron, M. (1992). Evaluation of a Random Breath Testing Initiative in Victoria 1990 & 1991, Report no. 39. Melbourne, Australia: Monash University Accident Research Centre.

Clark, J. (1999). The past: Hit and miss. In J. Clark (Ed.) Safe and mobile: Introductory studies in road safety. Armidale, Australia: Emu Press.

Corben, B., Peiris, S. & Mishra, S. (2022). The Importance of adopting a Safe System Approach—Translation of principles into practical solutions. Sustainability, 14, 5, 2559. (Accessed on 15 July 2025 at: https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/14/5/2559)

Cosmos (2025). SUVs and light trucks deadly to kids, cyclists, pedestrians. Cosmos, 14 May 2025. (Accessed on 1 September 2025 at: https://cosmosmagazine.com/people/society/suvs-and-light-trucks-deadly/)

DITCRD (2019). Review of National Road Safety Governance Arrangements. Final Report. Canberra, Australia: Australian Government, Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Cities and Regional Development (DITCRD). (Accessed on 22 July 2025 at: https://www.roadsafety.gov.au/sites/default/files/2019-11/stp_review_of_national_road_safety_governance_arrangements.pdf)

Encyclopedia Britannica (undated). Karl Friedrich Benz Biography. (Accessed on 2 July 2025 at: https://www.britannica.com/biography/Karl-Benz)

FORS (undated). The National Road Safety Strategy. Canberra, Australia: Federal Office of Road Safety (FORS), Department of Transport and Communications. (A copy of the strategy was tabled in the Queensland Legislative Assembly on 9 November 1993 and was accessed on 14 July 2025 at: https://www.parliament.qld.gov.au/Work-of-the-Assembly/Tabled-Papers/docs/4793t3398/4793t3398.pdf)

Hansen, R. & Bates, L. (2004). Mechanisms of Change: The Role of Parliamentary Committees in Road Safety. Proceedings of the 2004 Road Safety Research, Policing and Education Conference, 14-16 November 2004, Perth. Perth, Australia: Road Safety Council, Government of Western Australia. (Accessed online on 23 July 2025 at: https://eprints.qut.edu.au/11312/2/11312c.pdf)

Henderson, M. (1991). Education, publicity and training in road safety: A literature review. Melbourne, Australia: Monash University Accident Research Centre.

Hendrie, D. Lyle, G. & Cameron, M. (2021). Lives Saved in Low- and Middle-Income Countries by Road

Safety Initiatives Funded by Bloomberg Philanthropies and Implemented by Their Partners between 2007–2018. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18, 11185. (Accessed on 25 July 2025 at: https://researchmgt.monash.edu/ws/portalfiles/portal/371551330/371546540_oa.pdf)

Henstridge, J., Homel, R. & Mackay, P. (1997). The long-term effects of Random Breath Testing in four Australian states: A time series analysis, CR 162. Canberra, Australia: Federal Office of Road Safety.

History.com (undated). Model T. (Accessed on 21 July 2025 at: https://www.history.com/articles/model-t)

Historic Vehicles (undated). Historic car brands: Oldsmobile. (Accessed on 21 July 2025 at: https://historicvehicles.com.au/historic-car-brands/oldsmobile/)

Homel, R. (1988). Policing and punishing the drinking driver: A study of specific and general deterrence. New York, USA: Springer-Verlag.

Homel, R. (1990) ‘Random Breath Testing and Random Stopping Programs in Australia’, in R.J Wilson & R.E. Mann (eds), Drinking and Driving: Advances in Research and Prevention. New York, USA: Guilford Press.

Homel, R. (1993). Random breath testing in Australia: Getting it to work according to specifications. Addiction, 88, 27S-33S.

Homel, R., Carseldine, D. & Kearns, I. (1987). Drink-drive Countermeasures in Australia. Alcohol, Drugs and Driving, Vol. 4, No. 2, pp. 113-144.

House of Commons Library (2018). Road accident casualties in Britain and the world. Briefing Paper No. 7615, 23 April 2018. London, United Kingdom: Houses of Commons Library, Parliament of the United Kingdom. (Accessed on 21 July 2025 at: https://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/CBP-7615/CBP-7615.pdf)

Hyder, A.A., Hoe, C., Hijar, M. & Peden, M. (2022). The political and social contexts of global road safety: Challenges for the next decade, The Lancet, 400, 127 – 136.

Job, R.F.S. (1999). The road user: The psychology of road safety. In J. Clark (Ed.) Safe and mobile: Introductory studies in road safety. Armidale, Australia: Emu Press.

ICORSI (undated). Dr William Haddon Jr. (1926 – 1985). (Accessed on 8 July 2025 at: https://www.icorsi.org/dr-william-haddon-jr-1926-1985)

IFRC (1998). World Disasters Report. Geneva, Switzerland: International Federation of the Red Cross & Red Crescent Societies (IFRC).

iMove (undated). Micromobility. (Accessed on 24 July 2025 at: https://imoveaustralia.com/topics/micromobility/)

iRAP (undated). A world free of high-risk roads. (Accessed on 23 July 2025 at: https://irap.org/)

ITF (2008). Towards Zero: Ambitious Road Safety Targets and the Safe System Approach. Joint Transport Research Centre of the OECD and the International Transport Forum. Paris, France: OECD Publishing. (Accessed on 16 July 2025 at: https://www.itf-oecd.org/sites/default/files/docs/08targetssummary.pdf)

ITF (2016). Zero Road Deaths and Serious Injuries: Leading a Paradigm Shift to a Safe System. International Transport Forum of the Organisation for Economic Development. Paris, France: OECD Publishing. (Available online at: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/zero-road-deaths-and-serious-injuries_9789282108055-en.html)

ITM (2021). National road safety strategy: 2021-2030. Canberra, Australia: Infrastructure & Transport Ministers (ITM), Commonwealth of Australia. (Accessed on 14 July 2025 at: https://www.roadsafety.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/National-Road-Safety-Strategy-2021-30.pdf)

ITM (2023). National Road Safety Action Plan 2023–25. Canberra, Australia: Infrastructure & Transport Ministers (ITM), Commonwealth of Australia. (Accessed on 23 July 2025 at: https://www.roadsafety.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/National%20Road%20Safety%20Action%20Plan%202023-25_0.pdf)

Jones, A.W. (2022). An Appreciation of the Life and Career of Professor Robert Frank Borkenstein (1912-2002). Compiled by Professor A.W. Jones, PhD, DSc., University of Linköping, Sweden. (Accessed on 8 July 2025 at Microsoft Word – First page Borkenstein tribute 2022).

Johnston, I. (2010). Beyond ‘‘best practice” road safety thinking and systems management – A case for culture change research. Safety Science, 48, 1175–1181.

Khayesi, M. & Iaych, K. (2025). Second downward trend in global road traffic deaths. Injury Prevention (Epub ahead of print accessed on 26 January 2025 at: https://injuryprevention.bmj.com/content/injuryprev/early/2025/06/17/ip-2024-045487.full.pdf)

McLean, A. J. (2012). Reflections on speed control from a public health perspective. Journal of the Australasian College of Road Safety, 23(3), 51-59. (Accessed on 23 July 2025 at: https://journalofroadsafety.org/article/32695-reflections-on-speed-control-from-a-public-health-perspective)