The context of our work in road safety

Abstract

There are some major participants – such as governments and corporations – and some major social, economic and political systems which directly or indirectly influence the safety experienced by users on the road. The expert report to the Third Global Ministerial Conference on Road Safety in 2020 highlighted the need to broaden our perspective on road safety, who we work with and why we work with them. A wider appreciation of broader and overlapping or interconnected agendas such as physical activity, public transport and mental health is needed to make substantive road safety improvements.

We need to better understand and respond to the socio-economic determinants of safety. The World Health Organization describes these determinants as including: the social and economic environment, the physical environment, and individual income and social status. We also need to recognise and work to change the current approach to road transport safety which is bound by deeply embedded cultural norms. For example:

- The first tendency in law is often to identify blame for road trauma and not to address the contributing factors to the trauma.

- The primary element of analysis is the individual user/vehicle/road, rather than the systems which have influenced those elements and their interaction.

Speed management is a good example of how significant co-benefits can be generated between safety and many other societal outcomes, such as environmental and health outcomes. There are a variety of systems based analytical tools that can re-present road transport safety issues and opportunities, and a variety of stakeholders working on issues linked to road safety objectives. Identifying and working with these stakeholders is likely to bring substantial benefits.

The context of our work in road safety

For many decades, the unit of analysis in road safety was the individual road user. Issues to be addressed included the training and licensing of motor vehicle drivers, their knowledge and understanding of the road rules, compliance and penalty regimes to address illegal behaviour.

This made some intuitive sense – the problem is that people are killed or injured while using the road and there are a variety of good quality behavioural programs available to reduce road trauma. It also greatly limited the scope of action. There are typically individual errors involved in any casualty crash, but it was wrongly assumed both that these errors are the cause of road trauma, and that the road trauma solution required these errors to be addressed. We know much better than this now.

A primary breakthrough to this focus on the individual user was the consumer led vehicle safety campaigns in the United States of America. Ralph Nader’s searing analysis “Unsafe at Any Speed” argued that:

- Car manufacturers actively “resisted the introduction of safety features (such as seat belts)” and were “generally reluctant to spend money on improving safety”

- The auto industry’s creation of the “Three E’s” mantra (Engineering, Enforcement and Education) in the 1920s was a deliberate strategy to “distract attention from the real problems of vehicle safety” by placing the blame for accidents solely on drivers rather than on vehicle design flaws

- “Knowledge was available to designers by the early 1960s but it was largely ignored within the American automotive industry”, suggesting that safer cars were technically possible but not pursued for financial reasons.

Using a famous case study of the Chevrolet Corvair, the book had an instant impact. Less than 12 months after publication the landmark National Traffic and Motor Vehicle Safety Act of 1966 was signed into law, leading to a wave of institutional, regulatory and consumer reforms with significant safety benefits which are still being experienced today.

Yet the cultural reflex to expect that individual road users either demonstrate perfect compliance with masses of road rules, or open themselves to the possibility of grievous injury, remains to this day. Listen to public discourse regarding road safety, scratch a little at the surface, and reveal the victim blaming.

This chapter looks at the context of our work in road safety. The scale of the problem means we need to look at systemic change within the road transport system, but also the interaction of that system with a wide range of other societal influences. We look at the primary responsibilities for road traffic safety, the variety of ways in which these responsibilities are and are not being used to promote road safety, and some key external influences to the safety of the road transport system.

The road transport system

The road transport system is a major factor in the life of any neighbourhood, suburb, town, city, region or state in every country of the world. It is a major economic driver for small, medium, large and transnational companies alike. It is used for employees getting to and from work; for products received from suppliers and sent to customers; and for connecting all other transport modes – rail, maritime and aviation – to markets.

The system is used by people to gain the education and skills needed for the workplace, and for contributing to society in a much wider context. Outside of any particular economic relationships, the road transport system is used by communities, organisations, families and individuals to support all aspects of life.

Like water and power, it is difficult to anticipate what human life would be like without the road transport system. Unlike water and power, everyday use across the spectrum of human endeavour leads to persistent and extremely high levels of death and disability.

At its core, the road transport system provides the means for the movement of people and goods. However, for many decades, the collective focus of the system designers – governments, planners, vehicle manufacturers etc – was faster movement of more motor vehicles (commercial vehicles or private vehicles with few if any passengers). Major road infrastructure investments continue to be directed towards this view of transport planning, but change is occurring.

The change has been driven by many different factors, most obviously concern about global warming. The International Energy Agency estimates that motorised transport accounts for more than one third of all CO2 emissions and road transport for around 80% of those emissions. The agency’s first transport recommendation is to “Plan for compact urban development with improved public transport and infrastructure for micromobility and active travel”.

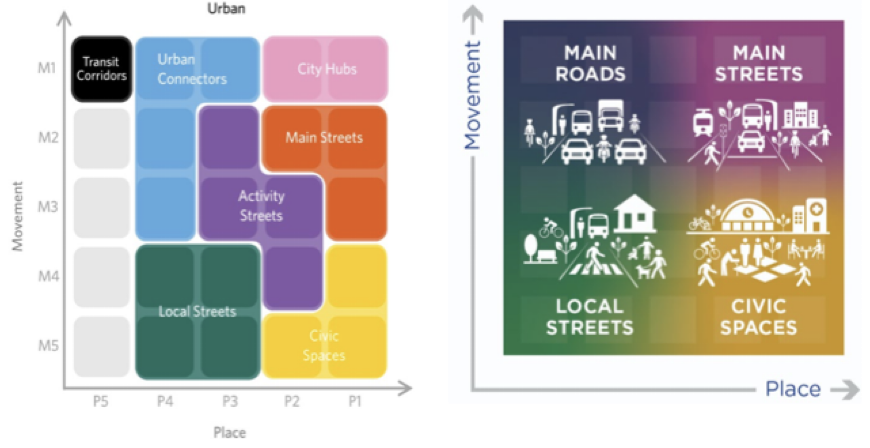

In Australia, New Zealand and elsewhere, attention is turning to recognising not just the movement function, but also the place function of the road transport system. This recognises that the road transport system includes places “that facilitate public interaction, meet people’s needs and serve as a meeting place where people spend time to carry out a variety of activities”.

This idea of “movement and place” allows for much greater recognition of the various demands of and expectations on the road transport system and is increasingly embedded in transport planning and management. It is consistent with ideas of sustainable mobility, which are directly beneficial to road safety through increasing the priority for safer modes of travel, such as public transport, or safer environments for the most vulnerable users, such as children and pedestrians. Figure 1 provides illustrations of this concept as it is being applied in New South Wales (NSW) by Transport for NSW and New Zealand (NZ) by NZ Transport Agency.

Figure 1: ‘Movement and Place’ in New Zealand (left) and New South Wales (right)

Source: [Insert here] Major safety environmental and economic losses will continue until systemic reform of the road environment occurs because it provides a foundation within which the whole road transport system can function.

Other key elements layer over the top, such as:

- The various people who use the road environment

- The various vehicles which are used in the road environment

- The speed with which vehicles are operated by people

- The transport systems which carry people and goods

- The regulatory environment within which each of these elements function

- The investment into increasing safe and decreasing unsafe aspects of the system.

There is a growing public policy realisation that the design and management of the road transport system itself is leading to very high levels of road traffic injury. Road safety professionals need to consider the interaction of all these elements, and more.

Authority, responsibility and power

In the continued shift beyond from the individual user, and the victim blaming this so often lapses into, it is important for road safety professionals to consider the critical functions and responsibilities organisations and institutions have in relation to road safety. The ubiquity of the road transport system means that few if any organisations do not have a significant role to play. Some play much more influential and powerful roles than others.

Organisational responsibilities for road safety can be categorised in a variety of ways, such as:

- Governments (elected officials and agencies such as transport and police), which reinforce societal expectations, establish and enforce regulatory boundaries, provide transport infrastructure and manage public safety resources

- Organisations such as manufacturers of vehicles, personal devices, and in-vehicle systems; telecommunications companies; social media platforms; and advertising companies which produce technologies and services that may increase and decrease safety risks to different degrees

- Employers and organisations which use these technologies or services and establish workplace policies and practices, including fleet operators, transport companies, and many other organisations whose operational decisions affect the level of road safety risk and trauma

- Civil society stakeholders including researchers, safety advocates, community representatives, educational institutions, media organisations, industry and professional associations, and insurance companies that influence public awareness, driver education, risk assessment, and policy development.

This is not to infer that individual road users do not have agency in regard to their own safety. They encounter and constantly mitigate various hazardous and risky situations while using the road network, making decisions within the broader context of systemic influences. Regrettably, while individual users are able to navigate the vast bulk of their interactions on the road without incident, there is insufficient protection when something goes wrong, leading to often catastrophic safety results.

Organisations and institutions hold primary responsibilities for a safe road transport system. Authority, responsibility and power flow through government agencies (including local or regional government), industry groups and delivery mechanisms, combining to influence and control the system that is actually used by individuals. Individual user experience can then feed back up the levels of authority, responsibility and power, to ensure unsafe outcomes are eliminated over time.

The road safety professional needs to consider these various responsibilities within the road transport system when considering how to address the road safety problem they are facing. Amongst all participants in the road transport system, government holds the greatest levels of authority, responsibility and power. Sometimes these powers have already been reinforced and delegated through other means to organisations outside government who carry their own responsibilities.

The climate for road safety

Successful safety reform has almost always been preceded by addressing the social, political and cultural climate in which the reform can be considered. It needs to be recognised that the climate for road transport safety is bound by deeply embedded cultural norms – for example:

- The first tendency in law is often to identify blame for the final operator error and not to address the underlying contributing factors to the trauma

- The primary element of analysis is the individual user/vehicle/road, rather than the systems which have influenced those elements and their interaction.

Safety is a core cultural value across society, but simply promoting a safety benefit is insufficient, particularly if organisations are asked to change some aspect of their operations or individuals are asked to “lose” a perceived “freedom”. Safety reform needs to be couched within a wider expression of societal goals.

Meaningful reductions in road trauma often require strategies which directly challenge perceived wisdom about road safety or accepted safety failures. It also often requires attention to changing the climate in favour of safety, making it easier for decision governments, elected representatives or institutional leaders to make significant safety positive decisions.

This is difficult and requires a well considered approach. For example, car centric transport planning and design has directly influenced urban and regional planning. This has ended up promoting population sprawl which is accommodated by new infrastructure and often perpetuates the car centric planning. This has long lasting implications by continuing to increase motor vehicle traffic volumes which increase exposure to road traffic injury. In this context, road safety professionals need to support change in urban and transport planning priorities, as well as promote safety specific reforms of unsafe legacy road transport systems.

Safety reforms inevitably reflect the current social, political and cultural context, but must be able to generate some enduring value in terms of longer term safety goals. Some situations (such as change of decision maker, or a particular safety catastrophe) can lead to major reforms being implemented, or to introducing an initiative which can piloted and then scaled-up. They may be more or less palatable at different times. The most effective road safety professionals have a short list of key safety principles and a long list of high potential safety options which can be delivered when the opportunity presents itself.

A wider appreciation is needed

Road safety professionals need to consider what the responsibility of different organisations to the specific safety problem is and engage them on how they can address the issue as part of their core business. But consideration is also needed of a wider set of issues which have an indirect but nevertheless direct bearing on safety. Some of these are physical activity, public transport and mental health.

Some major social, economic and political systems and trends also directly or indirectly influence the safety experienced by users. For example, income is a key risk factor for road traffic injury – poorer people are more likely to be injured, for a variety of reasons such as use of less safe cars (older, with fewer safety features), or living closer to main roads with less provision of safety infrastructure. Different work patterns also have different impacts upon safety, such as the rise of micro delivery services.

The World Health Organisation has a focus on the “socio-economic determinants” of health, and safety. These include: the social and economic environment, the physical environment, and individual characteristics and behaviours. These factors range widely between generalised issues such as the impact of poor economic conditions on safety programs, to specific issues such as unregulated or poorly regulated alcohol markets.

Income and social status, education levels, social support networks and health services all have an impact on safety outcomes for people within the road transport system. Gender issues are another major factor with decisions by women and girls about use of transport modes directly impacted upon by personal safety while using public transport, or at night.

More broadly, it is important to recognise some of the overlapping societal systems and trends impacting on road safety, such as:

https://www.who.int/news-room/questions-and-answers/item/determinants-of-health

- Health and wellbeing systems – for example, the quality of health promotion activity and trauma response capability

- Urban and regional planning systems – for example, urban sprawl and the location of essential services within the community

- Transport and mobility systems – for example, increasing the prioritisation of active modes, and moving away from car-centric mega projects

- Justice systems – for example, the relative impact of penalties on vulnerable communities with fewer mobility options

- Drug and alcohol production/consumption – for example, the level of control over the distribution and supply of alcohol.

Linking safety with other programs

Road safety is closely linked to several Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which were agreed and adopted by United Nations Member States in 2015. SDG 3 Good Health and Well-being includes Target 3.6 to reduce road traffic fatalities and injuries by 50% by 2030. SDG 11 Sustainable Cities and Communities includes target 11.2 to provide access to safe, affordable, accessible, and sustainable transport systems for all, including improving road safety. In addition, road safety initiatives contribute to achieving other SDGs like poverty reduction, gender equality, economic growth and climate action. This highlights that road safety is not just a transportation issue, but that it is more broadly linked to sustainable development, impacting areas such as health, well-being, and social equity.

Road safety simply cannot be advanced in a policy vacuum or “silo”. There are many policies that link with road safety, some of which exist outside of what is traditionally considered “transport”. This issue was highlighted as a key outcome from the Third Global Ministerial Conference on Road Safety in Stockholm in 2020. Resolution 2 of the Stockholm Declaration, ratified by national ministers and heads of delegations committed to:

“Address the connections between road safety, mental and physical health, development, education, equity, gender equality, sustainable cities, environment and climate change, as well as the social determinants of safety and the interdependence between the different SDGs, recalling that the SDGs and targets are integrated and indivisible”.

The Fourth Global Ministerial Conference on Road Safety in Marrakech in 2025 reinforced this need for improved understanding of links between road safety and other policies is likely to open new opportunities for implementing safety outcomes. Efforts are now required to ensure these opportunities are embedded in road safety strategy and actions.

Although consideration of these broader stakeholders adds some complexity including a requirement for increased engagement, linking to these areas provides many opportunities, including additional funding, political interest and expertise. This is particularly true when different policy areas have shared objectives.

This is more obvious when considering transport-related policy linkages. Three simple examples illustrate this point, although there are many others.

- When constructing new roads, safety should be embedded in the design from the outset. However, these safety benefits are not always adequately considered or included in planning decision making about designs.

- Asset managers widen the roadside (the ‘shoulder’) to prevent the road surface from breaking up from traffic use. However, this same activity also produces road safety improvements, as this additional road space allows a margin of error if road users stray from their lane. However, this joint benefit is often not considered when developing budgets and priorities for road upgrades. Greater consideration may lead to a different priority for road upgrade projects at no extra cost, but with a much greater societal benefit.

- Similarly, provision of improved public transport has obvious benefits for accessibility. However, there may also be significant road safety benefits, as public transport is the safest mode of road transport.

It is becoming increasingly clear that road safety professionals must actively engage with a much wider set of stakeholders.

Exploring linkages through speed management

Some of the linkages with policy areas outside of transport are less obvious. Improvements in the management of speed provides a useful example to explore this issue.

Speed, whether travelling above the speed limit or too fast for conditions, is considered a significant contributor to road trauma. Estimates are that speed may be a significant cause to more than half of all road deaths (Fondzenyuy et al., 2024). Therefore, improvements in speed can bring about significant safety benefits. Even small changes in speed produce substantial benefits, with every 1% reduction in speed estimated to result in a 4% reduction in fatal crashes, and a 3% reduction in serious injury (Elvik, 2019).

Management of speed has significant links to other policy outcomes. These linkages have been documented in several studies as has the need to work more closely with a broader group of stakeholders to help achieve joint benefits (Turner et al., 2024; Austroads, 2025). Some of the linkages include that reduced speed can:

- Reduce carbon emissions contributing to decarbonization objectives

- Reduce other emissions that have negative health impacts (NOx and PMO)

- Reduce fuel consumption, helping with cost of living

- Increase perceptions of safety, leading to a shift to healthier modes of travel such as walking and cycling, which in turn can produce significant health benefits, including reduced obesity

- Reduce noise, which can be harmful for mental health

- Improved traffic flow and reduced congestion through smoother driving and reduced intermittent delay from road crashes

- More pleasant living environments, which can also impact positively on social connections within communities

- Increased economic activity in shopping precincts or through more attractive environments for tourism

- Reduced impact on wildlife

- Potential for lower premiums for insurance.

⁶ One further linkage between speed reduction and journey time requires a brief mention. It is often assumed that reductions in speed limit will result in significant increases in journey times, and this has been a major barrier to change. However, an extensive evidence base now exists showing that the impact is often far less than expected, and there are even situations where speed limit reduction can lead to improved journey times (Turner, 2025).

individual component failures to the complex interactions within a system. The approach has been applied to road safety, including by Salmon et al. (2016).

In their review, Salmon et al. (2016) identified those responsible for road safety in Queensland. The process involved adapting the STAMP framework (control structure levels) to the road transport system in Queensland, and identifying key stakeholders (actors and groups) and the control and feedback loops that existed. Information was gathered from existing documents, and through input from stakeholders. A five-level model was developed, including Parliament and legislature (Level 1), Government agencies, user groups, industry associations, courts, universities (Level 2), Operational delivery and management (Level 3), Local management and supervision (Level 4) and Operating process and environment (Level 5).

The model indicates different control mechanisms between actors and organisations at different levels, as well as feedback mechanisms and decision-making authority. The model also includes broader Australian societal and international context that impacts the road transport system in Queensland. One key benefit from the assessment made in Queensland is the identification of contributors to road safety from outside those who are traditionally considered as system managers, and the inclusion of other actors and organisations.

The STAMP framework encourages a wider understanding of linkages, extending beyond drivers and road authorities to include vehicle manufacturers, urban planners, policymakers, law enforcement, insurance companies, educators, and even media organisations. This approach helps identify new leverage points and stakeholders—such as urban designers who influence walkability, technology companies developing in-vehicle alerts, or public health bodies advocating for safer behaviours—who can collectively contribute to road safety outcomes.

Conclusion

There are some major participants – such as governments and corporations – and some major social, economic and political systems which directly or indirectly influence the safety experienced by users on the road. We need to apply this understanding when working with organisations, and also broaden our perspective on road safety, who we work with and why we work with them.

A wider appreciation of broader and overlapping or interconnected agendas such as physical activity, public transport and mental health, and the socio-economic determinants of safety, is needed to make substantive road safety improvements. We also need to recognise and work to change the current approach to road transport safety which is bound by deeply embedded cultural norms.

There are a variety of systems based analytical tools that can re-present road transport safety issues and opportunities, and a variety of stakeholders working on issues linked to road safety objectives. Identifying and working with these stakeholders is likely to bring substantial benefits.